Travellers and Sound System Protest: Matthew Smith’s Visual Commentary

Staffordshire University (UK)

<http://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2019.11.01.13>

Protest and resistance have been an integral part of the UK underground dance music culture since its emergence at the end of the 1980s. This relationship has been documented by Matthew Smith, who began photographing the events and people involved while studying his undergraduate degree in Stoke-on-Trent, the home of Shelley’s Laserdome and other dance clubs. Many of his photographs are hosted on his archive website, which includes images from Glastonbury 1989, the anti-Criminal Justice Bill marches in the early 1990s, the Mother Free Festival of 1995 and more. From the outset, his photographs have presented the co-operative, resistive and celebratory aspects of the scene without judgement and from a position of support and solidarity. To consolidate his photo archive and promote the images to a wider audience Smith crowdfunded and published his first book, Exist to Resist (ETR) (2017), which comprises a collection of images he captured between 1989 and 1997. The timeline of ETR straddles the stages between the rave scene’s liberating genesis and its later inevitable stance of defiance and protest. The book’s preface describes the mood of the time.

That culture of celebration also was a product of opposition and resistance to the political policies and leadership of the time. The images in these pages deal specifically with the eventual criminalisation in law of that culture, after it had been rejuvenated and popularised by rave in a way that threatened government and its dictatorial control of democracy (Smith 2017: 6).

The leadership referred to is the UK premiership of Margaret Thatcher and, in this context, her government’s ideological and legislative assault on the free festival and traveller communities. Smith’s earliest photographs are from Glastonbury 1989. This was the first year large sound systems set up on the festival site, when Glastonbury was still a destination for travellers from the Peace Convoy. A selection of Smith's photos are presented below, followed by a brief interview about his work and plans.

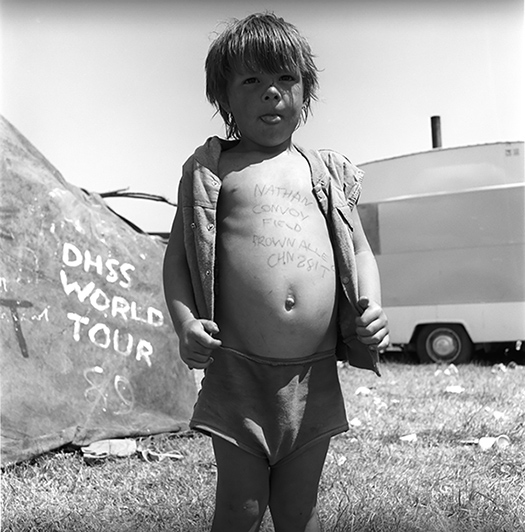

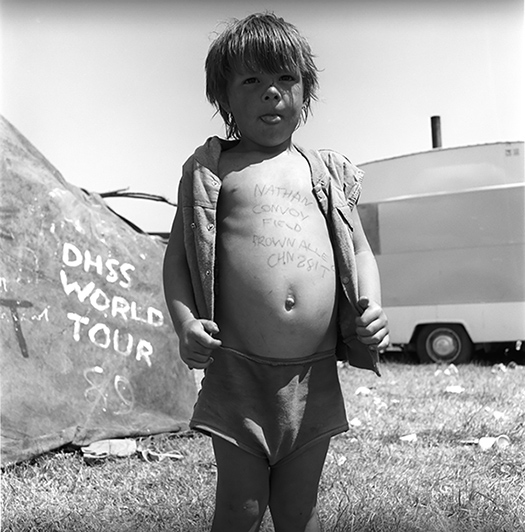

Figure 1. Nathan Convoy Field Glastonbury 1989. A young boy, Nathan, has his name written on his chest in biro detailing his name location and the registration of his parents’ vehicle. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

Figure 2. Blim Bros Sound System Set Up in the Traveller’s Field outside Glastonbury Festival 1989. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

After a hedonistic few years and the proliferation of sound systems and parties, epitomised by the Castlemorton Free Festival in 1992, the authorities began a stricter suppression of the traveller lifestyle. Legislation was introduced aimed specifically at outlawing sound systems and gatherings. This led to a series of protests against the proposed criminal justice act (CJA) of 1994. The first such event, in March 1994, was characterised by peaceful protest, dancing and celebration, with no noticeable civil unrest. Smith recalled,

The march set off in a massively carnival atmosphere and we were allocated a position at the rear by the stewards. There were a couple of rigs, one a customized Bedford CF by Desert Storm. People were looking on in amazement. There was impromptu dancing to our music on the streets of the capital. The back of the truck was crowded and bouncing. Down Marble Arch and into Piccadilly we went, occasionally halting for stragglers and latecomers to catch up, occasionally urging forward to keep the crowd together (Smith 2016a).

Figure 3. The 1st Anti CJA March. Trafalgar Square, London, 1 March 1994. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

Figure 4. 1st Anti CJA March. Trafalgar Square, London, 1 March 1994. Members of Sunnyside Sound System with their pink flag depicting an image of a Friesian cow going by the name of Liberty the Sacred Cow. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

Spirits were high after the first march and word of mouth ensured the second protest was larger with more sound systems in attendance. Despite a small contained disturbance, when some protestors scaled the gates of Downing Street and mounted police waded in on the crowd, it was again a largely peaceful event.

Figure 5. Exodus sound system from Luton on a lorry playing rave music as it passes in front of the Houses of Parliament during the 2nd Anti CJA Demo in London. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

Figure 6. A large group of people and vehicles leaving Hyde Park as part of the 2nd Anti CJA Demo in London. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

By the third march, authorities were intent to clampdown on the protests. In response to the largest crowd yet — an estimated 100,000 protestors — police presence was greatly increased (Smith 2016b). The carnival atmosphere turned violent as mounted police attacked and dispersed the crowds. The CJA was passed into law shortly afterwards.

Figure 7. Two girls dancing to Smokescreen Sound System in Park Lane outside Hyde Park during the 3rd anti CJA demo. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

Figure 8. A Protestor in front of a group of armoured riot police outside the Grosvenor Hotel in Mayfair during the 3rd anti CJA demo. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

These previous photographs represent a selection from Smith’s archive and ETR book. He has continued to document more recent festivals and events in the UK and Europe, sharing them mostly via social media. One example of Smith’s recent work is a series of images he captured at the anti-Brexit march in London April 2019. This march saw the formation of the Stop Brexit Sound System (Doherty 2019), with performances by DJs including Norman J, AKA Fatboy Slim and others.

Figure 9. Protestors with the Stop-Brexit Sound System, London, April 2019. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

Figure 10. A colourfully dressed protestor at the stop-Brexit March in London. Photo Credit: Matthew Smith (2019).

Dave Payling: When and how did you get the idea for the ETR book?

Matthew Smith: Back in 2012 I finally managed to sell my house in Bristol after a decade of struggling to keep it after the last housing bubble broke just after I bought it. There was some money left over from the sale. It wasn't enough to use as a deposit for another mortgage. That combined with the harsh fact that new financial regulations barred me from even applying for a mortgage for another six years because of the irregularities with the previous one left me with some significant life choices.

Considering my work and my future as an artist led to the decision that I had to develop the work that made me unique. Nobody to my knowledge had the comprehensive historical document of the late 80s/90s rave/protest DIY culture that I had made during the time we were running Sunnyside, our free party sound system collective.

During those times we made events, film, photography and graphic informational works in the form of what we called infotainment to help perpetuate our culture and oppose the plans of government. We also took part in a considerable amount of non-violent direct action in pursuit of standing up for what we believed in, taking part in many of the 90s protests and helping to create a nationwide tour of nightclubs and Student Unions across the UK to help create an awareness of the civil liberties implications of the impending legislation.

So, post Bristol I found somewhere cheap and anonymous to live, acquired a scanner, built a studio and spent the next four years scanning all my negatives to make the images visible and useable. I published the resulting galleries on social media. They received major feedback. Mostly the public response was how they illustrated the loss of cultural freedom that had occurred in the course of a generation. The next clear outcome was to make a book. So I wrote and made a film for a Kickstarter to fund the project and Exist To Resist just took off from there, receiving worldwide media support during its making from Russia through Europe to the USA and Australia.

Do you have any follow ups to ETR planned?

MS. 558 copies of the 1st Edition of 1100 were purchased in advance during the Kickstarter and the rest sold out very quickly with no traditional marketing or retail. The V&A (Victoria and Albert Museum) have acquired a copy for their library. Jeremy Corbyn bought a signed copy. During the Kickstarter Ken Loach supported the work, and the book helped form the visual reference during the making of his production company's latest movie about 90s rave culture in Scotland called Beats, directed by the immensely talented Brian Welsh.

That is a clear indication that there should be a 2nd Edition. It would provide an opportunity to improve on the original and to reach a much larger audience. 80% of the funding from the crowdfunder came from my own social media community. The initial years of my work frame a much larger and more diverse historical narrative that tracks the course of the evolution of our modern festival industry to the present day.

It is ironic that a criminalised culture has been appropriated as possibly our most popular creative industry. In a very real sense 1994's CJA served a very Thatcherite purpose to enclose a culture and impose market forces, state regulation and taxation on what was previously a very democratic and successful cultural phenomenon made by ordinary people.

I have a lot of ideas for further monographs, zines and multi-media exhibition outcomes in my mind that I would love the opportunity to develop. It's not advisable to share them in detail right now in public because ideas are a precious commodity and for the time being it's better to keep them out of the public domain. One thing I can say is that rave culture created a great, fantastically talented community and I would like to use the book to emulate this and continue to create an artistic, performative and intellectual community dedicated to producing culturally challenging creative output in order to generate future history.

With this in mind we have been working towards launching a CIC[2] called Future History Inc. The work received HLF[3] recognition and support not so long ago and that needs expanding on through the CIC. There is also Arts Council funding to access. The object of the CIC will be to preserve, celebrate and share the history of the archive in a public legacy. The work will also form part of the backbone the UK's first Museum of Youth Culture to be launched this summer by my long partners at Youth Club Archive. It was an invitation in 2012 to help found the archive with my work that helped significantly in making the decision to fund the production of the Archive.

Last summer in conjunction with the ISRF[4] I was invited to All Souls College in Oxford to host a work/study presentation day to an invited audience of academics around the question of law, who makes it and what is it for in order to provoke new perspectives and potential avenues of research.

What other future plans do you have?

MS. Right now, the immediate future is both exciting and extremely nerve wracking. In a matter of just a few weeks I will be celebrating thirty years of documenting Glastonbury Festival by going to work there for an amazing production company called Block 9 documenting their brand new environment concept at the festival called IICon. I have a very distinct idea to produce a book from that work in time for their 50th anniversary next year.

Pretty much straight after that I am putting the finishing touches to a major summer show in London. The Saatchi Gallery have invited me to be a core element of an exhibition called Sweet Harmony which is due to open on July 12th at their massive space in Chelsea. The show is due to run for two months and has a fantastic complimentary roster of artists involved. For the last two years we have been in long term negotiations with a couple of major show venues to produce a show from the book but I have to thank the Saatchi for stepping in and making Exist to Resist on the walls of a gallery into a reality.

Dave Payling is Associate Professor in electronic music at Staffordshire University in the School of Computing and Digital Technologies. He is a video music composer and holds a PhD in visual music composition. Dave also produces and performs electronic music and is integrating this more closely with his academic research. He is From the Floor section editor for Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture.

Website: http://payl.co.uk/

Doherty, Simon. 2019. "The DJs Fighting Against Brexit and for a People’s Vote". Vice (blog), 26 March. <https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/nexpwx/djs-peoples-vote-march-second-referendum-feature> (Accessed 23 July 2019).

Smith, Matthew. 2016a. "1st ANTI CRIMINAL JUSTICE BILL MARCH ’94 — Matthew Smith". Mattkoarchive. 28 February. <http://www.mattkoarchive.com/blog/2016/2/28/1st-anti-criminal-justice-bill-march-94>. (Accessed 23 July 2019).

———. 2016b. "3rd ANTI CRIMINAL JUSTICE BILL MARCH ’94 — Matthew Smith". Mattkoarchive. 28 February. <http://www.mattkoarchive.com/blog/2016/2/28/3rd-anti-criminal-justice-bill-march-94>. (Accessed 23 July 2019).

———. 2017. Exist to Resist. London: Youth Club.

[1] Matthew Smith, personal communication with the author (on Facebook), 5th June 2019.

[2] A community interest company (CIC) exists to benefit the community rather than private shareholders.

[3] The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), recently renamed the National Lottery Heritage Fund, provides grants to sustain and transform the UK's heritage

[4] The Independent Social Research Foundation (ISRF) is a public benefit foundation dedicated to the promotion of interdisciplinary research in the social sciences.