Transformation Through Connection? Insights From a Pilot Study of Story Sharing Cubes at Burning Man Events

University of Tartu (Estonia)

Aalto University (Finland)

<http://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2020.12.01.07>

Thank you all these people for making this happening. Thank you sun for making this wonderful day happen and making my dream come true, to be able to play and even in such a vulnerable state, without energy at all—still being able to get everything up and have the energy to play a four hour set. That’s beyond my own energy, that was something else.

This story was recounted by a participant of the 2019 Borderland event in Denmark, a weeklong participatory event of more than 3,000 people. The quote is part of a longer narrative by two musicians awaiting the sunrise atop the hill on the event site after a long day and night. While they were compelled to play their music on that hill, transporting their sound equipment from their camp up the steep incline was a mission impossible. Much to their enchantment, however, random strangers pitched-in to carry the instruments, including an electric guitar and a piano, to the top of the hill. They eventually created an improvised 4-hour performance during the sunrise, an experience the storytellers described as magical.

This is just one among a multitude of profoundly meaningful experiences that participants encounter at events like The Borderland, which follows the principles of Burning Man and has no formal organizational structure, managerial body or employees. These intense, potentially “transformative” experiences might be so insightful that some consider them life-changing. We believe that these types of stories reveal the essence of participatory cultural events, where participants act as contributors, not as customers of a “festival”.

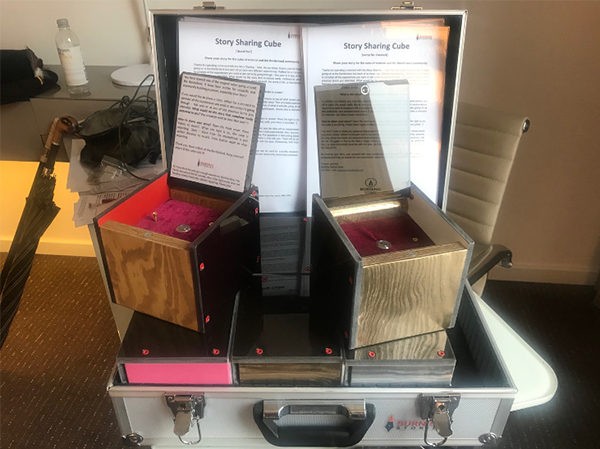

As researchers, we aren’t likely to have encountered this story by conducting interviews with a limited number of people. We heard this story thanks to a novel data collecting device, the Story Sharing Cube (see Figure 1). In this article, we share some preliminary findings from the pilot application of this new method that enables data collection in the form of stories. We also discuss the potential of the wider application of the method, such as in COVID-19 crisis areas or other fragile environments like war zones, that pose extreme challenges to data collection (Haer & Becher 2012).

Since its inception with a handful of participants in San Francisco in 1986, Burning Man has grown into an annual gathering of 80,000 participants in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert (see St John 2018), and evolved into a worldwide network of regional events, such as The Borderland. Previous research on this fast growing community has typically applied the methods of participant observation, interviews and post-event online surveys.

We searched for ways to reach a wide spectrum of random respondents, while at the same time trying to understand Burning Man events on a phenomenological level. In an attempt to investigate the diversity of experiences, our aim was to explore: What are the most meaningful event experiences that participants consider worthy of sharing? But the challenge was to collect the data in an environment where traditional surveys and interviews are usually difficult to conduct. For this, a team of scholars, artists and tech-experts from the Burning Stories research collective[1] co-created a device called the Story Sharing Cube (SSC).

Encountering these cubes in Black Rock City (BRC) 2019 and Burning Man regional events, The Borderland 2019 in Denmark, and Burning Bär 2020 in Berlin, participants who opened the box, found simple instructions along with the consent request to participate in the research, and a single button. Upon pressing the button, the recording begins. The simple design that we labelled as a hippie-proof user interface, addresses the challenges of collecting data in a hectic festival environment (Ruane 2017). While we also tested the method with slightly different sets of questions, the central request to the participants was to share their most meaningful story from the Burning Man events they have attended.

Figure 1. A Story Sharing Cube at Burning Man in the Black Rock Desert, Nevada, 2019. Photo credit: Terje Toomistu (2019).

This novel art-meets-science approach builds on the long-term commitment in several disciplines using personal narratives in qualitative research (Polkinghorne 1988). It follows the premise that people tend to attribute meaning to life and experiences through stories (Vaara, Sonenshein & Boje 2016). Narratives are normally collected in the form of an interview, or through textual analyses of diaries and autobiographies. We instead used a strange inanimate object—a cube. However, since the activity of sharing a story may have a self-affirming quality, we assume that our initiative also adds value to the participants’ overall experience of an event.

We also envision particular benefits of the method in the current era of “fundamental uncertainty” (Aven & Bouder 2020). Firstly, despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, transformational participatory culture events are organised in the future, but possibly with a change in terms of social distancing and also in the ways how people share their insights with each other. Therefore, in an environment that might highlight social distancing, applying a methodology that enables a socially distanced story sharing or feedback recording might be a way forward. Besides, the method might be a good addition or alternative to conducting in-person interviews and surveys during the event as it exhausts the field researcher considerably less.

While the potential and limits of this novel research method is a wider topic of discussion exceeding the scope of this paper, we will next share the preliminary outcomes of our pilot studies from three events. At BRC 2019, we placed 4-6 cubes at different locations, such as at certain camps or bars, as well as at the “trash fence” in “deep playa”,[2] of which the latter proved to be the most popular. Most of the shared stories were relatively brief. Of the 34 stories transcribed, the average length was 3 minutes, the longest 16 minutes.

Figure 2. A Story Sharing Cube attached to the “trash fence” at the end of “deep playa” at Black Rock City 2019. Photo credit: Terje Toomistu (2019).

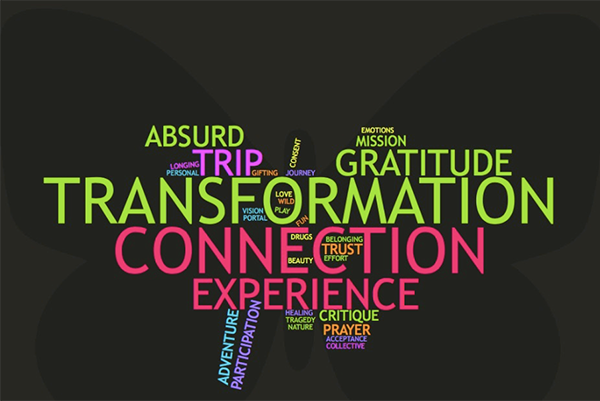

Following content analyses of the stories in our pilot, the two most prevalent keyword-codes appeared to be transformation and connection (see Figure 4). While transformation is perhaps unsurprising, given the nature of events that are often coded as “transformative”, and also the way our central question on the cube was posed (What is the Burning Story you would like to share?), the high prevalence of stories related to “connection” was unpredicted.

These narratives touched upon the theme of doing something together with others, when creating an enjoyable shared experience—such as spontaneously carrying equipment to play on top of the hill at sunrise. While the theme of connection was revealed in various ways, it was foremost expressed as a connection to other people. For example: “This was my first Burn and I immediately felt so welcomed by all the people”. Often this was expressed as simply highlighting a shared experience—“being here with you, together” or bringing a “virgin”[3] to the Burn. On several occasions, connection was very closely linked to transformation, sometimes perceived as a trust to connect:

I feel Burner culture has transformed me and helped me become a more open person, more capable of trusting people and connecting to them, and not being afraid to give as much as I can to people, to not fear that they’re just gonna take, but to trust that if I give a lot of things to other people, it will lead to connections that will enrich my life.

Figure 3. The Story Sharing Cubes. Photo credit: Jukka-Pekka Heikkilä (2019).

A particular connection appears through working for the benefit of others. This may be reflected in a brief testimony “building the temple for the people of BRC to have facility to express their joy”, or highlighting service to the community.

My story of transformation starts with my first Burning Man in 2010, and what specifically I think affected me the most was how generous everyone was. I was realising how all the art and the camps, and so many amazing experiences and gifts and things, were all made by the blood, sweat and tears of people for no reason other than to make other people smile and make other people happy, or give them a unique experience or help them grow, or just take care of their basic everyday needs so that they can focus on all that fun stuff while they’re there, and to me that was the most touching.

Connection was also expressed in more psychedelic, embodied and mind-altering terms, for example, by connecting deeply to one’s soul through dance, or connecting with the earth through mushrooms and with each other through singing, or through shared sexual activities, or a combination. For example:

And I asked them if they could give me pleasure, and it became a beautiful, sweet little orgy kind of thing, and then I gave everyone ketamine.

While it is true that mind-altering substances were mentioned a couple of times in the stories (although no-one explicitly shared a “trip report”), the abuse of substances was also critiqued.

A certain segment of the population is very focused on taking drugs and constantly talking about taking drugs and doing them every day and assuming that everyone else is doing the same. Probably because they are high all the time they don’t realize that actually the significant portion of the community don’t do drugs, or they only do them occasionally under special circumstances, or they only do very small amounts that aren’t that perceivable to others.

With regard to sexual connection, several stories (recounted by women) explicitly expressed the quality of platonic connections and the value of consent.

I just loved the way Burners are so platonically affectionate. You get so many offers for hugs and things like this, which just feels very caring and loving, and a lot of the hugs, you know, they’re really safe, they feel really genuine, like they just want to connect with you as you.

While the connections to others are sometimes recounted in relation to the perceived transformative experience, there are also other ways transformation is described. While the word “transformation” or “transformative” appeared frequently (11 times) in the stories, what was revealed as central to the stories are resolutions about one’s self and life.

These resolutions may involve a participant discovering their mission or role in life, whether that is about “enlightening people” or making others “have a little bit more fun in their life”. Or it may be a statement about an aspect of one’s life that needs some re-arrangement, such as “I need to stop working” or “I gotta love someone unconditionally, but my life and my dreams matter too”. Someone cited a newly found meaning of life: “The purpose of life is simple: seek joy!” The transformative qualities were less often projected on the more communal level. However, creating conscious communities, a collective vision, or taking the kindness received at Burns back to the wider society were mentioned.

Besides the deep personal reflections and vivid descriptions of meaningful shared experiences (i.e. connection), almost equally present were stories that highlighted a fun aspect of the Burn experience. These were stories about play, creativity, keeping it weird and going wild. One participant quoted lines from Hunter S. Thomson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, “We have two bags of grass, and 75 pods of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid, half a salt shaker of cocaine...”. Another shared a funky secret in just one line: “I got a finger put in my butt four years ago and I loved it”.

However, not all the shared secrets were fun or kinky. A couple of stories shared a personal traumatic growth experience. One person was coming to terms with a breakup when their ex was also present at the event. There was also a brief touching testimony of someone who was dying of cancer, but did not tell this to anyone.

Another unexpected aspect in many of the stories was the expression of immense gratitude—well exemplified in the quote at the beginning of the article. Sometimes it was explicitly addressed to the researchers who had placed the cube. But the gratitude was often directed to a much more abstract reference. This seems to be as much about a specific community (i.e. Burning Man, The Borderland) as about the gratitude of a living experience per se: “It’s incredible to be here, amazing journey, I love you”. Or: “Thank you so much, I couldn’t thank you enough”.

Figure 4. Word cloud created from the study’s content analysis keywords.

In conclusion, the Story Sharing Cube proved to be a fruitful method to collect a variety of narratives, opinions and reflections from event participants, for both scientific and community goals.[4] While acknowledging its limitations in comparison to other qualitative research methods such as interviews and participant observation, we see a great potential for the use of SSC not only at Burns and other participatory events, but at dance music festivals or conferences where people are expected to share their insights in a narrative format. SSC could potentially be a ground breaking data collecting device for extreme environments including COVID-19 crises areas, where traditional data collection is challenging or dangerous (Wainwright et al. 2018). Regarding event culture research in the COVID-19 era, methods enabling story sharing while practicing “social distancing” may prove highly useful.

The dataset of the pilot is intentionally narrow, therefore it is too early to draw any complete conclusions from the material. However, the theme of human connection and related transformation is certainly worth further attention. Exploring the collective sharing of narratives could also be a fruitful area for future research. Sharing all the collected data back to the community in the Burning Stories Forum supports conversation within the community, allows iteration of the methodology and increases communal participation as a whole. We are also planning to explore how the narratives from these events could inspire and comfort people suffering from the COVID-19 crisis.

However, should social distancing become the new norm at participatory culture events, we are likely to witness a shift in the centrality of the perceived transformation through human connection as our pilot revealed. The preliminary conclusions that underline the significance of human connection for participants at the Burning Man community gatherings hence echo concerns about the potential change of the transformative essence of these events in the post-COVID-19 world, leaving us to wonder what it would be like to Burn without meaningful connections with random strangers.

We express our gratitude to Hugi Àsgeisson from Blivande Stockholm for originally proposing the idea, Hilda Ruijs from Aalto University for currently conducting her thesis on the design of the cubes and The Borderland community for funding the materials of the pilot cubes. Particular thanks to Kalle Oja and Peter Tapio for building the cubes, to all participants who shared a story and to artist Mikko Heikinpoika (https://mikkoheikinpoika.com) for creating songs from the narrative data we shared back to the communities.

Figure 5. A Story Sharing Cube at The Borderland, Denmark. Photo credit: Hilda Ruijs (2019).

Dr Terje Toomistu is an anthropologist focusing on gender, affect and mobility based in Tallinn, currently employed as a research fellow at the University of Tartu, Estonia.

Email: terjetoomistu@gmail.com

Dr Jukka-Pekka Heikkilä is a scholar-activist focusing on extreme environments at Aalto University, Finland and the Story Sharing Cubes project lead.

Email: jukka-pekka.heikkila@aalto.fi

Aven, Terje and Frederic Bouder. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic: How Can Risk Science Help?” Journal of Risk Research: 1-6. <https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1756383>.

Haer, Roos and Inna Becher. 2012. “A Methodological Note on Quantitative Field Research in Conflict Zones: Get Your Hands Dirty.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 15(1): 1-13. <https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.597654>.

Polkinghorne, Donald, E. 1988. Narrative Knowing and Human Sciences. New York: State University of New York Press.

St John, Graham. 2018. “Civilised Tribalism: Burning Man, Event-Tribes and Maker Culture.” Cultural Sociology 12(1): 3-21. <https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1749975517733162>.

Ruane, Deirdre. 2017. “‘Wearing Down of the Self’: Embodiment, Writing and Disruptions of Identity in Transformational Festival Fieldwork.” Methodological Innovations 10(1): 1-11. <https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2059799117720611>.

Wainwright, Thomas, Ewald Kibler, Jukka-Pekka Heikkilä and Simon Down. 2018. “Elite Entrepreneurship Education: Translating Ideas in North Korea.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50(5): 1008-26. <https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18766349>.

Vaara, Eero, Scott Sonenshein and David Boje. 2016. “Narratives as Sources of Stability and Change in Organizations: Approaches and Directions for Future Research.” Academy of Management Annals 10(1): 495-560. <https://dx.doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1120963>.

Figure 6: Word cloud created from the transcriptions of the shared stories.

Figure 7. Artist-carpenter Kalle Oja and techie Peter Tapio building the Story Sharing Cubes 2019. Photo credit: Jukka-Pekkä Heikkilä (2019).

[1] Burning Stories research collective is an international team working pro bono to understand Burning Man and related participatory event cultures. We aim to radically blend science and the arts, both in scientific methods and results dissemination. Our ongoing research and activities include case studies of Burning Man art projects, surveys of communal coping and a conference that brings together a variety of backgrounds to explore the relationship between participatory cultures and capitalism.

[2] Deep playa at BRC in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert is the wide area that is the farthest from camping districts. The “trash fence” marks the boundary of the event.

[3] First time Burner.

[4] In addition to the stories collected with SSC, stories shared in text form are also gathered at the Burning Stories Forum.