Mexican Sonidero Sound System Culture in Times of Covid-19

RMIT University (Australia)

<https://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2021.13.01.12>

I am both DJ and researcher, and this article was inspired by my reflections during the first weeks and months of the worldwide lockdowns beginning in March 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic.[1] DJs/musicians in the "Global North"—including Australia where I’m based—were struggling to make themselves relevant as performers online. Meanwhile the Mexican sonidero (sound system) operators of the barrios (ghettos) amongst whom I’d done PhD fieldwork in 2019 and have inspired my work as a DJ/producer for 15 years, continued and expanded their already well-established online presence. This is because the sonideros (sound system operators) are well-accustomed to a significant part of their audience being in semi-permanent lockdown as undocumented workers stuck on the other side of the heavily militarised US-Mexico border. In light of an increasingly online existence for DJs and electronic music producers on a global scale due to Covid-19 restrictions, this article aims to emphasize the significance of how the particular Mexican sonidero practice has evolved online as a powerful creative response to the struggles endured by their dancing public.

As a DJ with a professional practice of 15 years, I am best known as a specialist of cumbia and music producer with the Cumbia Cosmonauts project. I grew up in working class rural environments in Switzerland and Australia, and first travelled to Mexico as a 22 year old in the early 2000s, where I lived a year as a student. I largely served my informal apprenticeship as a DJ participating in Australia’s “global post-rave counterculture” (St John 2009: 92), during which “I learnt to listen” in what can be considered as an informal apprenticeship (Henriques 2011: 88-122). Over the years I frequently returned to Mexico and my professional DJ/producer practice has evolved to heavily align with Mexican sonidero culture, although being based primarily in Australia. My PhD research on digital cumbia is practice-led and informs a DJ-as-researcher approach (Iten 2021b). During 2019 I spent time in the Mexican cities of Monterrey, Puebla and Mexico City, where the physical fieldwork featured in this article was experienced. Back in Melbourne, Australia, I have continued to engage “remotely” and “imaginatively” (Pink et al. 2016), primarily via the social media platforms of YouTube and Facebook where sonideros are most active. Being physically based far away from the main sphere of creative influence on my practice, I have become accustomed to primarily participating with sonidero culture online. Therefore, this research is informed by more than a decade of participant observation.

In Mexico, sonideros are part of a sonidera sound system culture that is parallel to that of Jamaica for example. Sonidera culture first emerged in the 1940s, with the convergence of new audio technology and cities exploding with poor rural migrants. The earliest sonideros collected mostly Afro-Cuban records, to which from the 1960s onwards Colombian cumbia was added and grew to become increasingly dominant. The cradle of cumbia is the northern coast and adjoining tropical hinterlands of Colombia. Cumbia became popular across Latin America from the 1950s onwards. In Mexico, cumbia proved particularly popular in the barrios, where sonideros transformed cumbia over several decades to become the slowed-down, synthesizer-driven and digitally produced cumbia sonidera (sound system cumbia) in the 1990s, which also became hugely influential across the Americas (Iten 2021a).

There are a handful of texts providing greater insight into sonidero culture, although this research is almost exclusively published in Spanish and written by cronistas (chroniclers) rather than scholars.[2] The recent documentary film Yo No Soy Guapo by Joyce Garcia (2020) is very much an invitation to dance, but it also shows the struggle for survival of the sonideros as a culture of the "street". This is an existential struggle, as the sonideros are in constant negotiation and battle with the authorities over doing events on streets, often the only public space accessible to hold these events representing the communities at home, of course, in the most precarious parts of the cities: the barrios.

Trailer Yo No Soy Guapo (Garcia 2018)

Sonidero culture is barrio-based and associated with the so-called "lumpen proletariat" (Manuel 1988: 18-19), who in Mexico are often compelled to emigrate to the USA as undocumented workers in order to survive. Hence there has been a lot of research focused on the sonideros as part of a "border culture" performed via saludos (shout-outs) by border-crossing sonideros or on mixtape recordings.[3] The significant online presence of sonidero culture has so far received little attention from scholars.

Sonideros operate as entrepreneurs, audio engineers and media entities and accordingly adopt the latest technology and adapt it to suit their specific needs. This included embracing the arrival of the internet and especially social media in the mid-2000s. On YouTube there are thousands of videos featuring live performances and a diversity of background videos, uploaded by sonideros and their supporters. Some compelling examples of footage which doesn’t feature live performances includes numerous videos of the arrival of trucks full of sound system equipment in remote rural villages.

Arrival of Sonido Master in Zacatipa, Guerrero (Chivas Montecristo 2011)

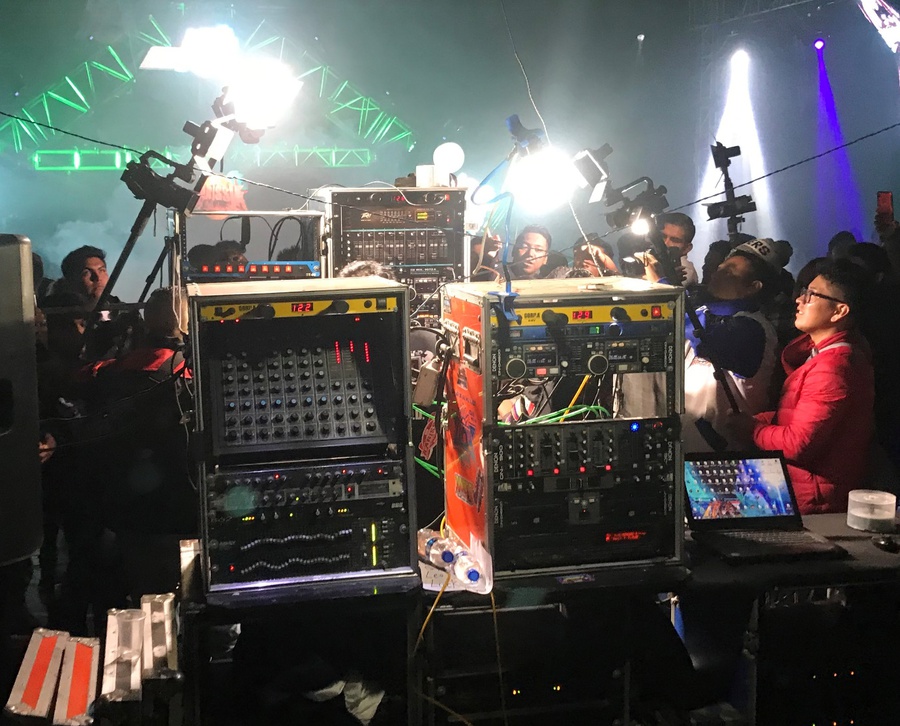

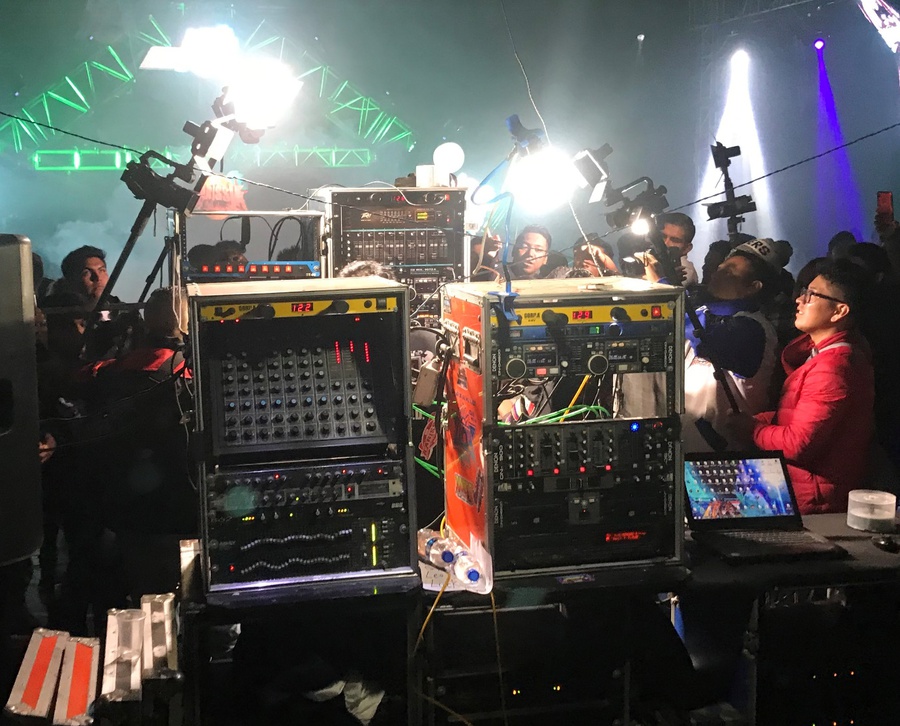

Since the first hand-held video cameras, footage of bailes sonideros (sound system dances) has been distributed in video cassette and DVD formats. This then continued online, and over the last decade an increasing number of YouTube channels have appeared dedicated to broadcasting sonidero culture. At a sonidero event during 2019 in the Mexican village of Tlaxcalancingo, just outside the city of Puebla, I observed at least six online broadcasters filming the performing sonideros (Figure 1). They were jostling to get as close as possible to the sonidero to provide an intimate view of their two-fold performance for those in attendance physically at the dance, and for those who were following the event online via live streaming or on demand videos edited and uploaded by the various broadcasters. There is such a wealth of footage available online; some events can be observed from the points of view of different broadcasters, and their creative presentation of the videos builds and heightens the online experience as parallel to the physical experience of the baile (dance). Many of those attending the bailes can be observed engaging with social media during the event. At the physical event, the sonideros are constantly being handed pieces of paper, posters and dancers’ smart phones with greetings meant for those in attendance as well as online. Simultaneously the sonideros are also responding to comments posted on their livestreams online.

Figure 1. Sonidero Performance Being Filmed in Puebla, Mexico. Photo credit: Moses Iten (2019).

One of the earliest YouTube broadcasting channels dedicated to sonidera culture is Richard TV, who started with a selfie stick posting the first videos in 2012 and has meanwhile grown to more than 4000 posted videos and close to 900,000 subscribers. The popularity of Richard TV can be attributed to the presenters’ journalistic flair and genuine curiosity about all aspects of sonidera culture. Richard TV pioneered the broadcasting of not just live footage from the dances, but also interviews with sonideros, sound engineers and dancers. An early hit on the channel is a documentary-style report featuring an interview with the audio engineer of Sonido Fantasma, which currently has 3.4 million views and elevated the interviewee—the audio engineer "Bomper"—to become a celebrity normally reserved for the sonidero owner-operators.

Audio Engineer Explains Sound System Setup of Sonido Fantasma (Richard TV 2017)

Since the possibility of live streaming has emerged in more recent years, this has arguably become the most significant part of the sonidero’s online presence. Depending on the profile of a particular sonidero, livestreams can attract thousands of viewers leaving hundreds of comments. This phenomenon created the space for online sonidero channels dedicated exclusively to the live streaming of broadcasts from a studio setting. During my fieldwork in Puebla in 2019, I was invited to perform as Cumbia Cosmonauts for one such channel, La Gargola Sonidera TV, who established themselves as a media entity broadcasting live videos via Facebook performed by local luminaries such as the late Sonido Samurai (featured in the video below), as well as up and coming sonidero talent and touring internationals. Samurai can be seen responding to the comments left on the Facebook page of La Gargola Sonidera TV, whilst assistants bring him other smart phones in order to respond to comments left on the same broadcast simultaneously being shared on other Facebook pages. Shout outs on La Gargola Sonidera TV are given to listeners in various barrios across the city of Puebla, gang members and people in prison, and most prominently the hundreds and thousands of people from the Mexican state of Puebla part of the emigrant diaspora of undocumented workers in the USA.

Sonido Samurai Livestream Performance via Facebook (La Gargola Sonidera TV 2019)

Millions of Mexicans have crossed, and keep crossing, the border into the US to look for work and, as already mentioned, sonidera culture has travelled with them. But once having overcome the hardship and danger of crossing the border without documentation, they are stuck and likely to be separated for many years from family back in Mexico. This immobility deserves to be recognised as a type of lockdown endured by millions of Mexicans (and undocumented people across the globe more generally). Accordingly, since at least the 1980s a vital part of sonidero culture as being barrio-based has been in facilitating the broadcasting and distribution of greetings and salutations across the border via physical recordings. In the 21st century, the bulk of these social connections have been broadcast online.

Evidently, sonidera culture has always had a big presence online, and when the first lockdowns were imposed across the globe due to Covid-19, their well-established online activity continued and expanded. Meanwhile here in Australia in early 2020, I could sense many people’s anxiety of not being able to travel or work freely perhaps for the first time in their lives. Even in a wealthy city like Melbourne which is globally renowned for its vibrant music scene, live musicians and DJs were particularly affected as their precarity has been spectacularly exposed during the Covid-19 pandemic (Strong and Cannizzo 2021). This impacted my own income as a professional DJ/producer and, whilst I faced similar anxieties to my Melbourne-based colleagues, I couldn’t help reflecting on how sonideros and their dancing public have always endured hardship akin to lockdowns in the precarious socio-economic reality of their barrio existence and more particularly as undocumented workers in the USA. Precarity is never hidden in the barrios, and with Covid-19 this precarity has only been intensified. Like Melbourne’s live music music scene, sonidero events have been severely restricted. Dances have been raided and stopped for not following measures such as the taking of temperatures, keeping distance, wearing masks, and so on. There are many prominent sonideros who have died directly or indirectly because of Covid-19. Beyond the existential impact on the sonideros themselves, it can be argued the greater the suffering in the barrio, the more vital sonidero culture becomes. During the first lockdowns in Mexico City, the well-known Sonido La Conga performed from his rooftop making neighbours dance on theirs.

Sonido La Conga Performing in Peñón de los Baños (Fleximania 2020)

During the pandemic, online broadcasting has grown exponentially, and continues to grow. In other research emerging of how electronic musicians and DJs have resorted to online broadcasting due to Covid-19 lockdowns “livestream fatigue” was documented, although ultimately overcome by broadcasting intimate moments from their daily lives (Sarkar 2021: 50-1). In the case of sonideros, this intimacy had already been exposed pre-pandemic by the likes of Richard TV. Perhaps the most notable change of sonideros livestreaming during Covid-19 has been the scale of their events. For example, some of the most renowned veteran sonideros, such as La Changa and Sonido Caribali, used to much bigger stages, could now be seen performing small, intimate and private events. Playing back-to-back with sonidero friends and joining the dancefloor to enjoy their own selections.

Sonido Caribali Back-to-Back Performance with Sonido Siboney, Mexico City (2021)

The more intimate online broadcasts during the lockdowns have emphasized the conviviality and bringing together of people which is so central to sonidero culture. Before the pandemic, emphasis was increasingly on the size of the dances and the audio-visual technology, but with the lockdowns even the biggest sonideros resorted to local events in private circles. These videos may portray precarity but have also served to remind us of the organization going on beyond the bailes as a form of mass entertainment, to see these as a love for music bringing together people as community meetings and nuclei of a way of resisting homogenous corporate and government sponsored culture. Reduced to the bare bones and seeing the sonideros dancing themselves, broadcasting from their rooftops and their patios are stark reminders of where the sonideros go once the glamour of the event is over. It’s now more important than ever to show solidarity and connection by contributing through online engagement, through documentation and through analysis and reflection. It’s my hope that there will also be new alliances, connections, tactics and strategies to make sonidera culture even more resilient in the future, when it's possible again to travel, and to dance.

Moses Iten is a DJ/producer and PhD candidate at RMIT University, Melbourne. He has toured the world with the Cumbia Cosmonauts project. His research focuses on sound system cultures, with a special interest in cumbia and Mexican sonideros. He is the Foreign Languages Editor at Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture.

Email: mosesiten@gmail.com

Cruzvillegas, Jesus. 2016. Pasos Sonideros. Mexico City: Proyecto Literal.

Delgado, Mariana and Marco Ramirez Cornejo, eds. 2012 Sonideros en las Aceras, Vengase la Gozadera. Mexico City: Tumbona Ediciones.

Henriques, Julian. 2011. Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques and Ways of Knowing. London and New York: Continuum.

Iten, Moses. 2021a. “The Roots of Digital Cumbia in Sound System Culture: Sonideros, Villeros, and the Transformation of Colombian Cumbia”. Journal of World Popular Music 8(1): 77–101. <https://doi.org/10.1558/jwpm.43089>.

Iten, Moses. 2021b. “The DJ-as-Researcher Approach: Methods Emerging Through ‘Digital’ Cumbia Fieldwork”. Dancecult Conference. Staffordshire University (UK)..

Manuel, Peter. 1988. Popular Musics of the Non-Western World. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pink, Sarah, Heather A Horst, John Postill, Larissa Hjorth and Tania Lewis. 2016. Digital Ethnography. Los Angeles and London: Sage.

Ragland, Cathy. 2013. "Communicating the Collective Imagination: The Sociospatial World of the Mexican Sonidero in Puebla, New York and New Jersey". in Cumbia! Scenes of a Migrant Latin American Music Genre. Héctor Fernández L’Hoeste and Pablo Vila, eds. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Sanchez, Pedro. 2019. Textos Sonideros (1999–2019) Vol. 1: Cronicas. Mexico City: Ediciones Negis-Teodis.

Sarkar, Pradip. 2021. “Being a DJ in a Time of Zero Social Huddling: Tales from a Locked-Down India”. Perfect Beat 1(1):47–55. <https://doi.org/10.1558/prbt.19347>.

St John, Graham. 2009. Technomad: Global Raving Countercultures. London: Equinox.

Strong, Catherine and Fabian Cannizzo. 2021. "Pre-existing Conditions: Precarity, Creative Justice and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Victorian Music Industries". Perfect Beat 12(1):10–24. <https://doi.org/10.1558/prbt.19379>.

Wirz, Mirjam. 2018. Ojos Suaves/Soft Eyes: Sound System Cumbia from Mexico to the World. Translated by Delphine Tomes, Brendan Flannery and Moses Iten. Mexico City and Zurich: Mirjam Wirz.

Amigos Suscribanse A Nuestro Canal De Musica Sonidera. “Los Jinetes De Chuchito Vera ((Lucky Wepa )) Sonido Lucky Star—Tlaxcalancingo Puebla 2019”. Youtube, 6:39. Uploaded on 27 August 2019. <https://youtu.be/oFv0k2MTxjE> (accessed 18 November 2021).

Amigos Suscribanse A Nuestro Canal De Musica Sonidera. “Es la Cumbia de mi Tierra Peñon de los Baños—Sonido la Conga—Concierto En La Azotea 2020”. Youtube, 7:56. Uploaded on 12 May 2020. <https://youtu.be/unSgWm-P3qY> (accessed 12 November 2021).

Chivas Montecristo. “Llegada De Sonido Master Armando Cuatle En Zacatipa Gro”. Youtube, 7:03. Uploaded on 22 August 2011. <https://youtu.be/7EMPcB6KUmw> (accessed 19 November 2021).

Dancecult. “Moses Iten – The DJ-as-Researcher Approach: Methods Emerging Through ‘Digital’ Cumbia Fieldwork”. YouTube, 21:41. Uploaded on 12 October 2021. <https://youtu.be/QR2yGPDfkho> (accessed 12 November 2021).

Joyce Garcia."Yo No Soy Guapo". Vimeo, 81:00. Uploaded on 1 May 2020. <https://vimeo.com/ondemand/yonosoyguapo> (accessed 24 November 2021).

Richard Tv. “Asi Reacciono Sonido Siboney Cuando le Enseñó Este Tema Sonido Caribali De Willi”. YouTube 17:00. Uploaded on 23 May 2021. <https://youtu.be/fJv2DDx4hts> (accessed 22 November 2021).

Yuli Rodriguez. "Trailer Yo No Soy Guapo". Vimeo, 7:03. Uploaded on 19 January 2016. <https://youtu.be/7EMPcB6KUmw> (accessed 23 November 2021).

[1] This article is based on a paper I presented at the “SSO#7 Sound Systems at the Crossroads” online conference in July 2021, hosted by the Sound System Outernational research group based at Goldsmiths University, London.

[2] The role of cronistas is particular to Latin America and their cronicas (chronicles) are considered as a type of engaged investigative journalism or intellectual engagement with popular culture. The anthology Sonideros en Las Aceras, Vengase La Gozadera (2012) edited by Mariana Delgado and Marco Ramírez Cornejo as part of El Proyecto Sonidero, brought together scholarly analysis with cronistas and sonideros writing about their culture. Notable latter publications include those by Mirjam Wirz (2019), Jesus Cruzvillegas (2016) and Pedro Sanchez (2019).

[3] Cathy Ragland’s (2013) research on the “sociospatial world” of sonidero culture connecting the Mexican state of Puebla with the US states of New York and New Jersey is particularly notable.