Kaos, Kilowatt and Ketamine: A Cultural History of the Free Tekno Movement

Independent researcher

<https://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2023.15.01.07>

As a researcher with a keen interest in exploring subcultural dance movements, my current focus is the earliest communitas to which I belonged: the free tekno movement. This journey began during the turn of the millennium when I took my initial steps into the European underground rave scene. My research aim is to trace the evolution of this vibrant scene over time, seeking to understand its development and the various factors that have contributed to its transformation. In this article, I will introduce the historical and theoretical foundations of my research. The primary objective of this project is to chronicle the cultural history of the free tekno movement, from its very beginning until the present. However, this essay is not intended to be a detailed literature review of the phenomenon.

In the period from 1990 to 2005, Italy, my country of origin, emerged as a prominent destination for traveling sound systems coming mostly from the UK and France. These sound systems discovered Italy to be a hospitable and accommodating location for their trucks and parties, making it a significant hub in the subculture.

During my youth as a punk enthusiast, I spent my free time in an extraordinary village situated near Rimini, my hometown. This village, known as Mutonia, and which still exists, represents a permanent autonomous zone settled along the banks of the Marecchia River in Santarcangelo di Romagna, Italy. Mutonia is a community with a distinctive "Mad Max" aesthetic, and it has thrived since its establishment in 1990. This unique haven was birthed by a collective of punk travelers and artists who came to be known as the Mutoid Waste Company.

Figure 1. The “time-machine” sculpture in Mutonia. Photo credit: Giorgia Gaia (2021).

I was particularly captivated by the ambiance of the unconventional gatherings of the Mutoids. These weird parties provided the background for my initial forays into mind-expanding experiences in a post-apocalyptic setting. The folklore surrounding the early raves hosted in Mutonia between 1990 and 2000, evokes tales of extended psychedelic cyberpunk odysseys. These events were characterized by an eclectic mix of art, tequila and LSD, resulting in wild, endless journeys into the realms of altered consciousness.

As suggested by their name, the Mutoid Waste Company have a distinctive approach of utilizing the refuse of consumerist society to craft their giant mutant machines and spectacular sculptures. Born in 1984 in West London, stemming from the imaginative minds and skilled hands of Joe Rush, a punk artist, and Robin Cooke, a hippy mechanic. Over time, this artistic movement expanded to encompass a broader collective of punk artists, eccentric travelers and anarchists.

Figure 2. An artwork in Mutonia. Photo credit: Filippo Mozone (2019).

Throughout its history, the Mutoid Waste Company's artistic visions materialized in diverse geographic locations, leading to what Joe describes as a “huge absurd bit of anarchy” (Rush 2015). One illustrative example of their unconventional actions is depicted in the image of Tankhenge, a rendition of Stonehenge constructed from tanks, alongside a Mig 21 aircraft stolen from a Russian Army camp. This audacious creation took shape during the winter of 1990, shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Figure 3. Tankhenge, a Mutoid artwork in Berlin (1990).

Figure 4. A Russian Mig 21 aircraft transported in Berlin by the Mutoids (1990).

Upon their arrival in Santarcangelo di Romagna in 1990, a countryside town in close proximity to Rimini, the Mutoids made quite an entrance with their science fiction inspired costumes and unconventional vehicles. They immediately occupied a parcel of land where they commenced expressing their art through mesmerizing fire performances and astonishing mobile robots. The local residents, having never encountered anything similar before, quickly developed an appreciation for this peculiar and distinctive manifestation of human creativity.

Figure 5. A robot constructed with recycled material in Mutonia. Photo credit: Giorgia Gaia (2017).

Figure 6. An art corner in Mutonia. Photo credit: Giorgia Gaia (2021).

However, in July 2013, the Santarcangelo di Romagna Municipality issued an order calling for the "demolition" and "restoration" of the state-owned area housing Mutonia. This decision led to the emergence of a protest movement advocating for the Mutoids and opposing the eviction of Mutonia. This movement gained momentum on a national scale, eventually reaching the Italian Parliament. In response to the widespread protests and the recognition by the Superintendencies of Bologna and Ravenna of the Mutoid community as a "bene cittadino" or cultural asset, the Municipality of Santarcangelo, in February 2014, reversed its earlier eviction order. As a result, the Mutoid community was granted ownership of the land, recognizing it as an artistic treasure to be preserved.

Video 1. The arrival of Mutoids in Santarcangelo di Romagna. The Mutoids Invade Us. (1996).

The style of events orchestrated by the Mutoids throughout the years, can be considered as the archetype of a free tekno party: illegal, mainly with electronic tribal music, radical street theater, surreal science-fiction means of locomotion, techno-punk-inspired costumes, terrifying monsters that move around spitting fire (Cooke 2001).

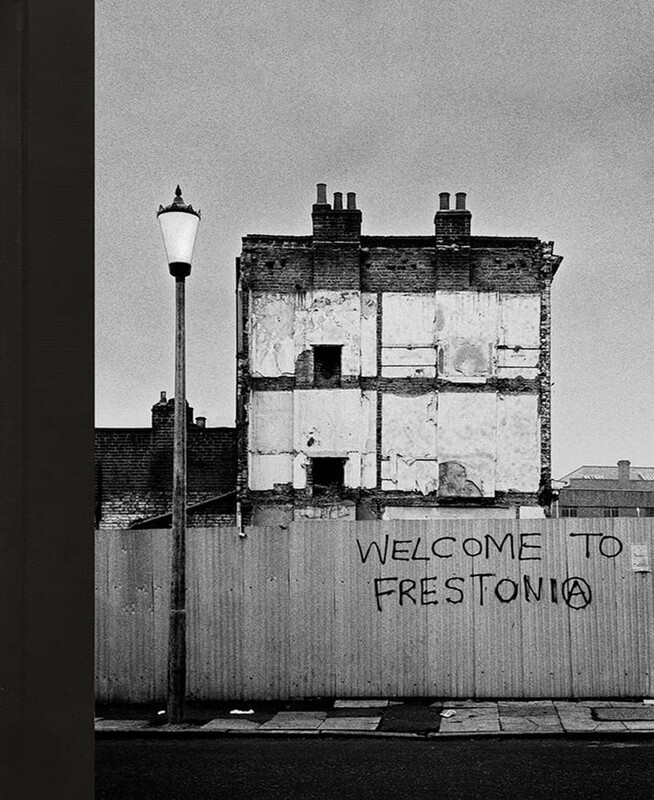

To gain a deeper understanding of the historical origins of the Mutoid Waste Company and, by extension, the free party scene, it is relevant to delve into the history of Joe Rush. Joe Rush, alongside fellow Mutoids, spent their formative years in England within a highly unique countercultural milieu known as Frestonia. Frestonia was the adopted name of the inhabitants of Freston Road, an area in London that had been squatted and self-declared the Free and Independent Republic of Frestonia. This is the very site where The Clash recorded their legendary album, Combat Rock, in 1982. Within this tiny republic, various lifestyles merged, encompassing the excesses of the punk movement, with the “Apocalypse Hotel” serving as a favored venue.

Figure 7. The Clash standing before the Apocalypse Hotel, Freston Road. Photo credit: Pennie Smith (1982).

Figure 8. The entrance of Frestonia squatted area. Photo credit: Tony Sleep.

Several of the founding members of Frestonia were actively involved in the creation of the Albion Free State Manifesto, which was published in 1974. The text of this manifesto can be found in the booklet titled "Rehearsal for the Year 2000". Notably, the manifesto's opening articles encapsulate its foundational principles:

- The only state is your state of mind and the only government is your body;

- The world is a common treasure house for all. Use your birth certificate as a credit card for: free love, free shelter, free food and freedom to do whatever doesn’t infringe the freedom of others. Money is the meanest measurement of human energy there is.

Figure 9. “Rehearsal of the Year 2000” booklet cover (1976).

Considering how and why the free tekno movement emerged as a countercultural phenomenon in England, subsequently spreading throughout Europe, it is essential to delve into the history of free festivals. Arguably, the first free festival in the UK took place in Shepon Mallet, a small town very close to Glastonbury, on 19th September 1970, just a day after the passing of Jimi Hendrix. With the name “Pop, Folk and Blues”, the festival happened at the Worthy Farm Pilton with a one-pound entrance fee, all farms milk free and sheltered fields for camping.

During the 1980s, a nomadic community of travelers was born, drawing individuals from diverse subcultures such as punks, hippies and the earliest ravers. This collective came to be known as the Peace Convoy, comprising approximately 600 people who identified as "new age travelers". Their journey culminated in the infamous Battle of Beanfield in 1985 when the Peace Convoy was en route to Stonehenge to establish their free festival. A police roadblock was located seven miles from their destination. The encounter resulted in numerous injuries among the travelers, with more than 500 of them eventually being arrested, constituting one of the most extensive mass detentions of civilians in the annals of English legal history (McKay 1996).

Figure 10. A “Peace Convoy” bus in Glastonbury (1986).

It was 1988, the Second Summer of Love in the United Kingdom. This time was characterized by the spreading of illegal parties set to the beats of acid house music and the distinctive sounds of the Roland 303 synthesizers. It was when a new substance decisively infiltrated the dance floors, significantly shaping contemporary dance culture—that substance was Ecstasy (Reynolds 2013).

Ecstasy brought about heightened sensations of love and empathy among ravers, and a notable decrease in various forms of violence. These gatherings evolved into a form of medicine for addressing social repression and feelings of alienation.

If the Mutoids were to become the artistic and aesthetic soul of the free tekno movement, then Spiral Tribe were the musical and spiritual epicenter of it. After the Second Summer of Love, a period marked by the resurgence of paid parties and clubs, Spiral Tribe defiantly declared their commitment to the illegal free rave scene. They promptly began organizing events across the United Kingdom equipped with their sound system (St John 2009).

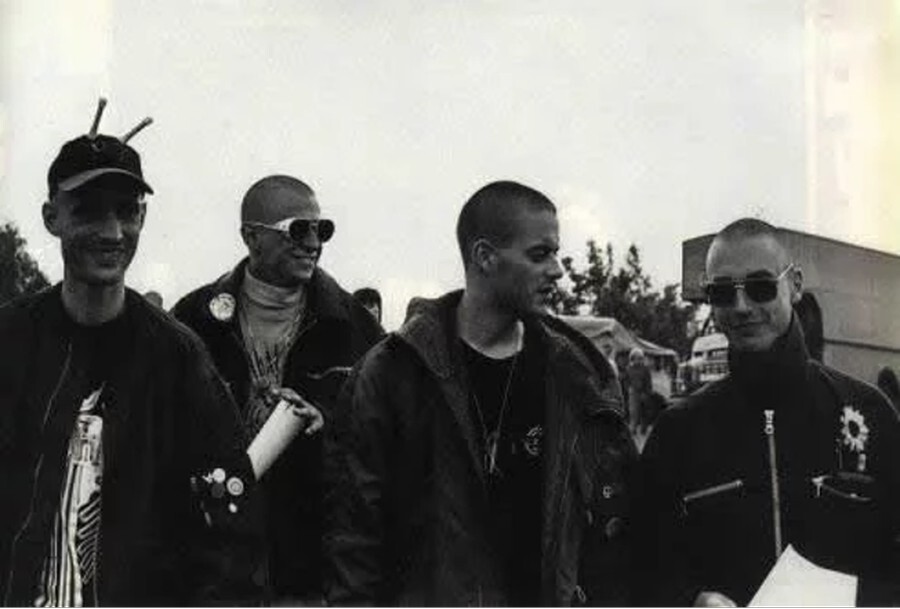

Figure 11. Mark Angelo, Sebastian Vaughan (69Db) and other Spiral Tribe members. Photo credit: Ariel Wizman (1992).

Their notoriety reached new heights in 1992 following the Castlemorton rave, during which Spiral Tribe, DiY and Circus Warp gave life to a temporary rave-town completely beyond the control of authorities. In the aftermath of Castlemorton, many members of the Spiral Tribe faced arrest; their vehicles and sound systems were seized. They were charged with conspiracy against the state, ultimately compelling Spiral Tribe to depart the United Kingdom.

Figure 12. Participants at Castlemorton rave. Photo credit: Alan Lodge (1992).

Figure 13. A sound system at Castlemorton rave. Photo credit: Alan Lodge (1992).

They transformed an old trailer into a legendary mobile studio named Studio 23, hosting resident producers Crystal Distortion and 69db, and they established their own record label: Network 23.

Spiral Tribe began their exile in Paris in summer 1993 when, together with other sound systems, they announced the first teknival. Their exile kickstarted the blossoming of huge, free, illegal teknival scene across Westernand Eastern Europe which influenced dance culture of more than a generation, including mine, of course.

My ongoing research project, which delves into the free tekno or teknival movement and the roles played by "kaos”, "kilowatt” and ”ketamine” as a triad of recurring cultural elements within the scene, commenced with the establishment of a conceptual and historical framework. The remainder of my essay offers a brief introduction to these three interwoven conceptual histories.

Following years of participant observation, in 2023 I started interviewing some of the movement's founding members, Debbie Griffith and Jeff 23 from Spiral Tribe being among the first. Presently, the research is still in its initial stages.

It's worth noting that the term "teknival" was actually coined by Debbie, one of the crew's founding members. In our interview, she explained that after their exile in France, they needed a name able to express their novel rave party concept. Consequently, she merged the words "carnival", "tekno" and "festival" to create "teknival".[1]

Et voilàle teknival.

Figure 14. The flyer of the first teknival (1992).

Teknivals predominantly feature electronic music and are characterized by radical art in the Mutoid style, independent sound systems and clandestine locations, often set amidst natural landscapes or within warehouse settings. These events are known for their extensive drug experimentation, free admission, lack of security or fences and a profound emphasis on both physical and mental liberation.

The use of the letter “k” in “tekno” primarily serves to distinguish the underground scene from the commercial one. Tekno music is generally faster than techno and was initially identified as hardcore tekno, but over time it has diversified into various subgenres. For many ravers, tekno represents the sound of rebellion and revolution.

One noteworthy aspect of the tekno scene is that the DJ typically performs behind the crowd or remains hidden behind the wall of the sound system, in stark contrast to most other scenes where DJs are on stage. This practice is rooted in the illegal nature of tekno events, where DJs prefer to stay concealed and anonymous. It also conveys an important message: in the realm of tekno, what truly matters is the music and the sound systems. On the dance floor, all individuals are equal, and the DJ is not idolized as in other genres. Tekno becomes a form of musical devotion.

Figure 15. The front of stage for DJ live performances and light controls in Tranzit sound system stage at Step Evolution, Czech Republic. Photo credit: Giorgia Gaia (2023).

From its inception, the teknival scene focused on challenging the conventional norms of the dance scene and worked towards the creation of ephemeral, chaotic realities fueled by idealism.

It was because the ages had been so oppressive and so materialistic and so conformist, rave showed the pure chaos of the human experience. It was mind blowing. And that’s why the government cracked down on it because it was dangerous to see. Suddenly everyone, black people, white people, rich and poor people, were together dancing under the same bloody sky in the same music.[2]

In the tekno scene, dancing assumes a political dimension, as the ability to travel with tech gear and set up a party spontaneously in any location represents an assertion of independence. Defending the human right to party became a means of reaffirming individual and collective freedom, effectively transforming hedonism into a form of activism. The entire tekno scene draws inspiration from radical anarchist concepts and the pursuit of authentic experiential freedom, often expressed through chaos.

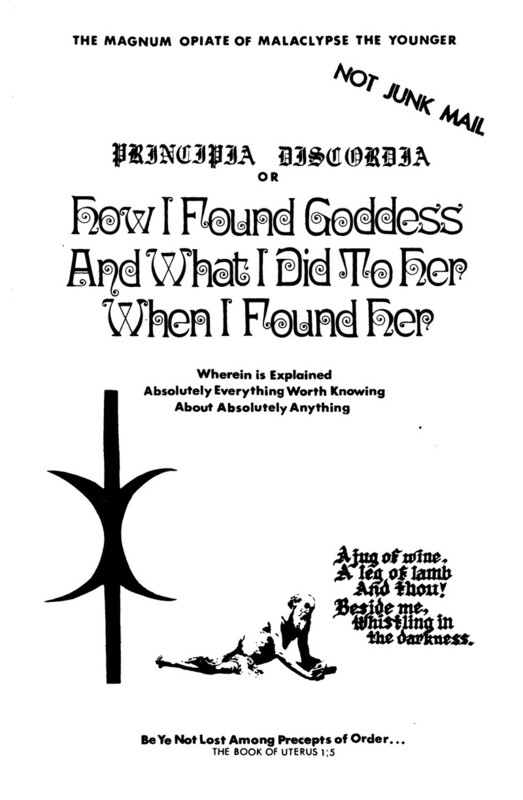

Within this movement, the number 23 holds significant spiritual importance, symbolizing chaos. Discordianism, for example, views 23 as the Holy Number associated with Eris, the goddess of chaos. Robert Anton Wilson also delves into the concept of the "23 enigma" or the "Law of Five" (Wilson 1987: 198). In our interviews, Debbie referred to 23 as "the cosmic joke that chaos is playing on us," while Jeff23 mentioned the influence of RAW’s writings. Jeff23 also mentioned how Psychic TV, with band leader Genesis P-Orridge, influenced the appearance of number 23 in the electronic music scene of the time.[3] In 1986, Psychic TV decided in fact to attempt a mission: release 23 albums on the 23rd day of 23 consecutive months. However, the series was discontinued after 17 albums.

Figure 16. “Principia Discordia” cover (1970).

A milestone documentary about this scene is World Traveller Adventures, released in 2006. Of the 4 episodes, one is titled 23 Minute Warning, which includes interviews with the members of Spiral Tribe.

Video 2. An episode of the documentary series “World Traveler Adventures” (Dentice and Noi 1993).

In this convergence of spiritual, rebellious and anarcho-chaotic philosophies, the everyday lives of ravers underwent a transformation towards a nomadic lifestyle. Their existence evolved into a continuous and immersive odyssey, passionately embarking on a continuous and immersive journey towards envisioned cyberpunk and utopian landscapes. In this context, the tribal nomadic lifestyle embraced by ravers exemplified their ontological anarchy, aligning with the vision put forth by Hakim Bey (1991). The "tribe" coalesced around the shared sense of belonging to a specific sound system, forging a close-knit community that embarked on this immersive journey together.

The term "kilowatt"(kW) serves as a measure of the power required to operate a sound system and is used to indicate its potency. Historically, the concept of the sound system can be traced back to 1950s Kingston, Jamaica, where it was born. These sound systems consisted of large speakers, generators, amplifiers and turntables, all loaded into the back of a van and transported to various neighborhood corners to provide the musical backdrop for street parties (Henriques 2011). During this era, very few individuals could afford to purchase their own records or radios, so sound systems became the primary means through which people discovered and enjoyed new music. Serving as a critical avenue for introducing new sounds to a broader audience, sound systems played a significant role in shaping emerging musical movements, as happened for the free tekno or teknival movement.

In the present day, the free tekno movement has evolved, and its radicalism has waned compared to its earlier days. The nomadic lifestyle is no longer as central to the movement as it once was, but the sense of community creation remains a fundamental aspect of its identity.

I have been collecting vinyls for years and we all decided to put all our vinyls in a library and to give up all money and put everything to go for the sound system, the trucks and our shared life. We were totally tribal. It was a proper community going on.[4]

Throughout the history of the tekno movement, numerous sound system crews or tribes have gathered under the motto "The only good system is a sound system". In recent years, teknivals have adopted a more competitive stance in terms of the amount of kilowatts (Kw) each sound system possesses. This sometimes leads to the creation of massive walls of speakers, resulting in an excess of decibels and, occasionally, a lack of creativity. The shift towards a focus on technology over the power of radical art in the tekno movement raises significant implications for discussions about technology, ontological anarchy and teknivals. These implications are areas that I aim to explore in the course of future research.

However, it's important to note that in its essence, teknival serves as a communal space of potentiality that encourages a complete experimental attitude. This attitude extends beyond music and art production and encompasses all aspects of social interaction.

Figure 17. A sound system wall at a teknival in Albania. Photo credit: Giorgia Gaia (2021).

Kilowatts are essential for producing music, and it is the music itself, along with its capacity to alter consciousness, that holds paramount importance in this context. Music and ASC have the unique ability to induce liminal trance states, rewiring human brains and facilitating profound transformations.

The sound system is the healer. The music is the healer. The revolution really has to come from inside you. It’s the change of consciousness. It’s not to go out into the fields and take fuckload of bad drugs. There needs to be a place for the free parties today.[5]

Alterations of consciousness have indeed played a significant role in the history of teknivals, with the consumption of mind-altering substances being prevalent. In the early days of the movement, there was an idyllic and profoundly psychedelic atmosphere. However, in time the scene became increasingly saturated with a wide variety of drugs, including some considered "bad" or harmful (D’Onofrio 2018).

The pirate ethos of the movement embraced the flow of illegal goods from different parts of the world, serving as a vital conduit for the distribution of both beneficial and harmful substances. Ravers from Eastern Europe, in particular, have mentioned that teknivals facilitated access to psychedelics and mind-altering substances that were otherwise challenging or impossible to find, such as LSD, DMT, MDMA and, of course, ketamine.

Debbie shared that as early as 1991, substances that were not widely known began to be discussed and consumed at their parties.

We were starting to hear rumours of this new drug called ketamine. Obviously, we couldn’t wait to try it. When it eventually arrived, I think it was about July or August 1991 in England. It was from a lab in Switzerland and it was fantastic. We absolutely loved it.[6]

Ketamine holds a central place in the tekno scene for two primary reasons. Firstly, it was within this context that the substance was first extensively explored and distributed for hedonistic and psychedelic purposes, finding a highly receptive environment. Secondly, it encapsulates the entire essence of the paradox associated with the use of substances with profound psychedelic potential for recreational purposes—the duality of altered states of consciousness.

Ketamine is “both a source of healing and harm, integration and disintegration” (Jansen 2000). Like many substances, it can be beneficial when used responsibly, but can become toxic when abused. Unfortunately, at the turn of the new millennium, coinciding with the expansion of the teknival scene in most European countries, a significant proportion of the community suffered from ketamine, opioid or cocaine addiction.

At the beginning of the millennium, teknival became a routine. During the weekends in France, Italy and Eastern Europe, thousands of individuals gathered for week-long raves, whether in squats, warehouses or forests. Bologna's Livello 57, one of the scene's prominent community centers, drew 10 to 15,000 people, myself included. In 1996, harm reduction experiments began in Italy, thanks to a collective called Lab57. Their primary focus was on drug-checking during large raves and parties and the promotion of Europe's largest self-organized anti-prohibitionist street parades, which continued until 2006. The first street rave parade in Bologna took place in 1997, in a collaborative effort of Lab57 and Mutoids.

Like the rest of the movement, Lab57 had a political stance on harm reduction. They viewed party substances as a cultural phenomenon rather than a social problem, recognizing their active role in the ongoing process of defining drug consumption and safety within society.

Figure 18. An info point curated by Lab57 during an illegal rave party (2013).

The increasing illegality of raves and the challenges faced by countercultural movements are indeed pressing issues. Many countries have taken stricter measures against unauthorized gatherings, particularly those involving a large number of participants. Moreover, the advent of the internet and digital surveillance has raised concerns about censorship and control. Countercultural movements that promote freedom of expression often find themselves at odds with governments seeking to maintain order and control over public spaces.

The tekno scene has historically faced opposition from authorities. However, for many participants, this struggle between chaos and order is where the spiritual and activist significance lies. It represents a form of resistance against oppressive forces and a celebration of individual and collective freedom.

As the tekno movement and other countercultures continue to navigate these challenges, they may also explore new ways to adapt, evolve and preserve their core values in the face of increasing restrictions and surveillance.

Figure 19. Policemen against ravers in CzechTek. Photo credit: Jan Zátorský(2005).

Giorgia Gaia is an independent researcher, with MA degrees in Cultural and Social Anthropology and in History of Hermetic Philosophy and Related Currents at the University of Amsterdam. Since her early twenties she has been involved in the underground scene of rave culture, as a DJ and cultural producer. Her academic research has focused on countercultures, esoteric communities, occultism and psychonautic. Being herself continuously involved in the creation of alter(n)ate realities and magickal experimentations, since 2013 she is co-curator of Ozora Festival’s cultural area. In 2018 she founded Occulture Conference, a Berlin based festival exploring occultism and esoteric arts.

Bey, Hakim. 1991. T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism. Brooklyn: Autonomedia.

Cooke, Robin. 2001. “Mutoid Waste Recycledelia and Earthdream”. In FreeNRG: Notes From the Edge of the Dance Floor, ed. Graham St John, 204–48.

D’Onofrio, Tobia. 2018. Rave New World: l’ultima controcultura. Fano: AgenziaX.

Henriques, Julian. 2011. Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques, and Ways of Knowing. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Jansen, Karl L. R. 2000. Ketamine: Dreams and Realities. Sarasota: MAPS.

McKay, George. 1996. Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance Since the Sixties. London: Bath Press.

Reynolds, Simon. 2013. Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture. New York: Routledge.

Rush, Joe. “Berlin”. Mutoid Waste Company. 10 August 2015. <https://cargocollective.com/MutoidWasteCo/Berlin>, (Accessed 1 October 2023).

St John, Graham. 2009. Technomad: Global Raving Countercultures. London: Equinox Publishing.

Wilson, Robert Anton. 1987. Cosmic Trigger: Final Secret of the Illuminati. Pennsylvania: New Falcon Publications.

Dentice, Alberto and Cesare Noi. 1996. The Mutoids Invade Us. Galeazzo Arcibaldo di Romagna. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5X4OuCsCKFk> (Accessed 1 October 2023).

Raclot, Damien and Krystof Gillier. 2004. The Spiral Philosophy: 23 Minute Warning. Uwe. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RuOFQThcrqw> (Accessed 1 October 2023).

[1] Debbie Griffith, interview with author (video call), 5 April 2023.

[2] Debbie Griffith, interview with author (video call), 5 April 2023.

[3] Debbie Griffith, interview with author (video call), 5 April 2023; and Jeff23, interview with author (phone call), 23 March 2023.

[4] Jeff23, interview with author (phone call), 23 March 2023.

[5] Jeff23, interview with author (phone call), 23 March 2023.

[6] Debbie Griffith, interview with author (video call), 5 April 2023.