From Spontinuity to Dream Seeds: My Journey with Lightshows from the Sixties to the Present

Independent researcher

<https://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2023.15.01.06>

It is said in some Western esoteric teachings that Universe is, in essence, a show of Light.

By this I understand that the “Light of the Soul” is the “Electric Fire of Spirit” made manifest in the physical realms, and the lightshow is a sacred embodiment of the ecstatic dance of minds at play.

Well, that’s how I experience it, anyway.

My history with lightshows begins with my father, an avid photographer who documented our travels in Panama, Europe and around the US as a family in the ’50s and ’60s. He found a way, in 1959, to make a reel-to-reel tape recorder change slides on cue with a music soundtrack and his spoken narrative. Truly funky old-time tech.

As a military family, we moved many times. By my high school years, we had settled in Colorado Springs. In the summer of 1967, on a whim and a ten-speed bicycle, I went to Drop City, an early (and seminal) communal arts experiment outside Trinidad, Colorado. Comprised of geodesic domes made from the tops of automobiles, it had been featured in Time magazine, alerting me to the local presence of hippies. Welcomed and offered a joint, I danced under my first “psychedelic lightshow”. I was invited to play with coloured liquids on a homemade overhead projector aimed at the triangles that made up the dome. Liquid lights entered my mind that first night.

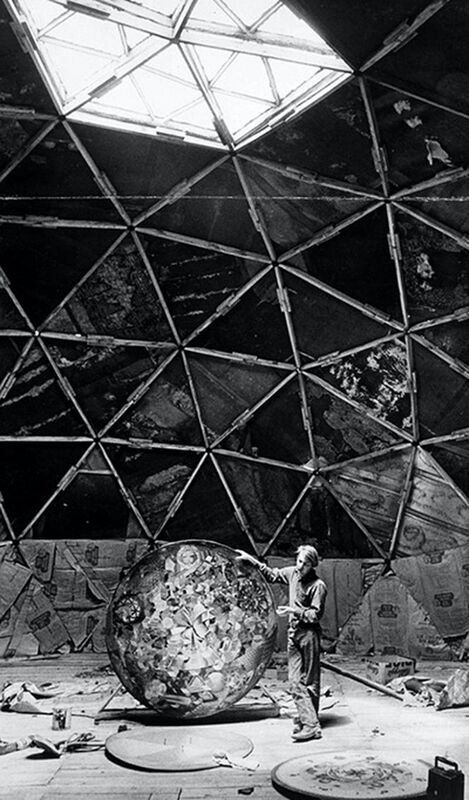

Figure 1. Clark Richert, co-founder of Drop City in the Performance Dome, with The Ultimate, a group painting that spun under a strobe light, revealing different images based on speed of strobe, 1967. Courtesy of Denver Post.

Figure 2. Author at dining table, Drop City, 1967. Courtesy of Denver Post.

Following high school and a brief sojourn at Pennsylvania State University, in the fall of 1967 I returned to Colorado Springs. There, I joined up with a ragtag “hippie family”. We pooled our resources and rented a former downtown strip club, painted glowing fluorescent fairies and wizards on the black walls, borrowed some projectors and with our house band Baby Magic, opened to a bemused public who did not understand what on earth we were doing. A Hippie nightclub? What?

Our first hippie nightclub, The Magical Kingdom of Endor, lasted only a few weeks. We soon found a better venue for our family: 1111 Pearl Street, downtown Boulder, Colorado.

Arriving in Boulder in early 1968, we discovered a small city at the inception of its hippie era. The new venue was on the second floor with a back alley entrance, a ballroom with a balcony and four small apartments that looked out onto Pearl Street. The new home for the Magical Kingdom of Endor (after the “witch” in the Old Testament who only used her magic for good) was quickly decorated and set up. We had a headshop in one apartment and lived in the others. The lightshow took over the balcony, facing the low stage at the head of the ballroom below. A group of Boulder artists (see bardomatrix.com) had preceded us with their lightshows. John Chick, one of the artists, dropped by one day. He was preparing to leave for Kathmandu and offered to give us an overhead projector. An amazing relic from a bygone era, John told us it had been used in New York for some of the earliest lightshows (possibly League for Spiritual Discovery, Timothy Leary’s lecture accompaniment). To this day, I have never seen another like it. Instead of a plastic “fresnel lens”, with concentric rings moulded into it to focus light, it had two 9” square optical glass lenses. It produced a brilliant image and was housed in a heavy black case. It became central to our array of light-manipulating techniques.

We added another overhead projector and two slide projectors with telephoto lenses and (wired) remote controls. I taped the controls onto the sides of the lenses. This enabled me to change slides while keeping my hands on the lenses. I used my fingers to “bend the light”, shaping, melting, morphing images that I could control with great precision. My buddy Herbie and I ran the lightshow. Herbie was an instant liquid light Master, somehow making forms appear unlike anyone I have known. Others worked with us at various times.

There is skill involved in working with liquid light. Envision two large clear glass clock faces, one a bit larger, nested together. In the bottom one are two clear liquids that do not mix, usually water and mineral oil. Colours are added to the liquids: food colouring in the water, and ink or dye in the oil. The smaller top clock face sits in the liquids. The top “plate” is held between fingers and thumb of each hand, just above the surface of the bottom plate, balanced and gently moved. The top plate can manipulate the liquids, causing it to flow, wash across, or take on shapes. Both plates can sit on patterns, such as pressed glass cake platters found in thrift stores, or cutout patterns. A skilled artist can create an endless assortment of shapes and movements. Effects such as using a straw held in the mouth and blowing on the liquids, or dripping more colours into the liquids add to the possibilities.

Figure 3. Clock face “dishes” with liquids, on overhead projector.

I had been a photographer for many years, and I spent what money I had on film to build an image library. I copied images where I could find them, and took many, many hundreds of slides of my own. I gathered a “Visual Database”, as it is called on my computer now. I collected a huge number of images from nature, artworks, faces, macro-photography. Placing two images on screen at once, morphing them into each other, then replacing one, morphing, replacing the other and on and on, consumes a steady supply of content. Consider that one image may be on screen for less than ten seconds, for a three hour show.

The art of the lightshow is quintessentially remix art, sampling the visually available universe as part of a process of unfolding the dense information matrix in which we live. The lightshow artist takes what exists—colour, liquid movement, moments of time (which is what a photographic slide is), moving images and light effects—mixes them in new ways and shares them with a happy and appreciative audience. It is ephemeral. As I see it, one need not be concerned that one’s art has been shown on screen for a few seconds as part of a lengthy montage. Art has always involved remixing sources, and the lightshow follows this long established method.

Figure 4. Mixed image of overhead projector dishes with liquids and fish.

The human perceptual system perceives but does not record movement well. The majority of memory is in the form of moments, still images. Slides projected on a screen are very close to what makes up our memories. We recall still images with little movement. This is our common experience, and the lightshow reflects this.

At Endor, during our stoned discussions about our role, aside from the techniques of colours and images (mixing and moving to accentuate the music), we realized we were working in two diametrically opposite ways. The liquids were impossible to replicate night to night. The movement of the dishes was intuitive, spontaneous, abstract, while the slides were images programmed to provide a loosely connected sense of narration. In trying to define what it was that we were doing, Herbie and I stumbled upon a new word: spontinuity.

Spontaneous Continuity. We were billed as Spontinuity from then on.

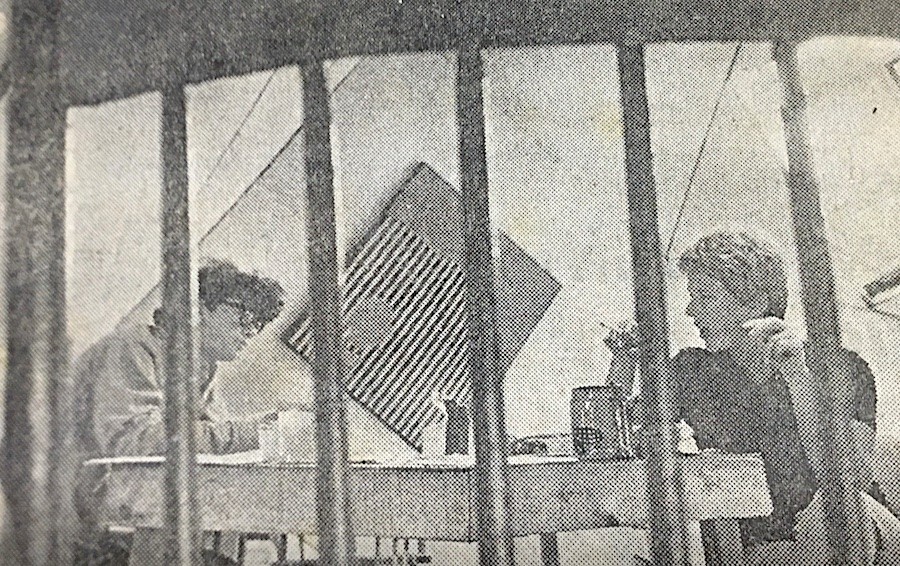

Figure 5. Business card for Spontinuity Lights: Marty Wolff, Scott Taylor and Charlie Morrell 1969 (Herbie missed the photo shoot!).

From their earliest days, lightshows have been described as “an attempt to replicate the psychedelic experience”. We found this ludicrous. Only psychedelics themselves can do that. So what were we doing? Clearly, we had a fantastic palette to work from and a potentially significant role to play in the culture in which we lived. We chose to see ourselves as one element in the alchemical process that opens the ecstatic state of celebration that is the live music event: rhythm, music, colour and light, swirling in a kind of “tribal” ritual.

Thematically, I programmed the show. Kodak Carousel projectors were my main tools. Each carousel tray could hold 80 slides (eventually increased to 140). I grouped slides under general themes and filled trays with these themes. I typically had eight trays for a show. If I knew some of the lyrics to the songs that were scheduled to be performed, I would find images to match. Otherwise, I had trays in reserve full of slides I was familiar with, and through my manual control of the lens, could shut off the image, release, remove and replace a tray for another better suited, and reopen the projector to continue the show without interruption. The transitions were key to the flow of a good show.

In addition, we found ways to warp light. The technique is called lumia. Flexible mirrors could warp and ripple images. Suddenly, an image that had been static could ripple as if on water, then morph into an image of the ocean. Mirror glass glued onto a flexible backing, then broken, could produce shattered reflections that escaped the screen on stage, traveling around the room in pieces.

We were working with images that were delightful, fun, thought provoking. We were careful with our imagery—nothing of a dark terrifying nature, only images that were uplifting and joyous, even mystically inspiring— were appropriate for our audiences.

Figure 6. Mixed image, mirrored dolphins and Flower of Life meditation.

Endor was a meeting place for the waves of hippies travelling cross country. The mountains offered places to camp, and Boulder became a hippie Mecca. Our house band, Baby Magic, opened for various local and traveling groups, such as Black Pearl, Alice Cooper, Conal Implosion, Zephyr and others. We served organic snacks and each of us wore costumes (mine was knee high moccasins, a flowing silk shirt, beads and an elf hat over my shoulder length hair).

Figure 7. Author, stoned, just after Endor was shut down. 1968.

After about three months, the town “leaders” accused us of bringing the hippies to Boulder. During our Friday and Saturday night shows, uniformed police stood on the sidewalk with “noise complaint” forms on clipboards, asking passing people to sign them. It did not take long for the local constabulary to close us down, but only after a City Council meeting where we tried to meet their arguments with reason. No dice. Within six months, having realized we were a solution to, not a cause of, the city’s “hippie invasion”, the council relented and offered some of us a purpose-built “youth centre” to manage. We declined; our family had by then disbanded, and we went our separate ways.

I went to Key West in the summer of ’68, and wound up living on the streets until I was picked up as the light artist for The Smiths, who had a three week gig at a local club. (This was the original American group named The Smiths, later just Smith, not the English group from the ’80s.) Money from that work and from selling my hotrod 1931 Model A Ford pickup truck brought in just enough to get off the streets and buy tickets for 6 hippies to go to Belize, where we wanted to buy an island. But that is another story.

When returning to Boulder in the winter of ’68-69, I resumed work in the lightshow scene. At that time, we found support from the University of Colorado Student Council to book bands and do shows. Bands included the Grateful Dead, Steve Miller, Eric Burdon and War, John Mayall and the local soon-to-be famous Zephyr, among many more.

Doing lights for the Grateful Dead was exceptional. As a jam band, their style included a song in which they “trade leads”, with each musician leading the others on improvisations. The Dead are the only band I have ever worked with who slowed to a common tempo, and together, all nodded to me and my partner to take the lead. They then played along as accompaniment to our spontaneous narrative imagery. It was a revelation to be let inside the performance, rather than being an adornment. It was a lovely gesture, one I have never forgotten.

Figure 8. Mixed by author, using “Stargate”, courtesy of Robert Venosa.

We were doing shows in the Glenn Miller Ballroom on the university campus. We had lots of extra projection surfaces. I found more slide projectors and put still images on the walls. I watched members of the audience in their altered states turn away from the stage to lie down and gaze at serene images of yoga postures, esoteric charts describing the “spiritual components of the Human”, sacred geometry, etc. These are the few images we used that contained words. They were well received.

Figure 9. A typical diagram for the back walls, for those seeking seeds for their personal quest.

I was asked by Eric Burdon and War to tour with them, performing concerts across the Southwest. The weirdest lightshow I ever did was with them at a US Air Force base outside Tucson, Arizona, where about fifteen people showed up at the high school auditorium. The band treated it as a dress rehearsal and just kept on rockin’. The tour only lasted a few weeks before I returned to Boulder.

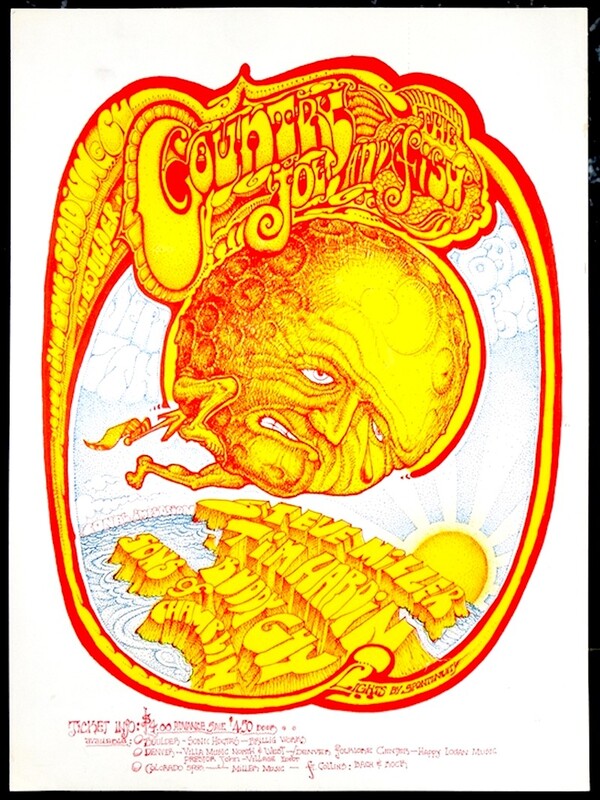

On 9 July 1969, we did the first large scale concert/festival in the University of Colorado’s Folsom Stadium, called the Moon Bowl. The event featured Country Joe and the Fish, Steve Miller, Sons of Champlin, Tim Hardin and Buddy Guy. The lightshow consisted of 12 artists under my direction, using 21 projectors and ran for almost six hours, non-stop. It began with a liquid projection of a black screen that resolved into a galaxy of bubbles, morphing into the spectrum, out of which appeared a 16mm animated film we made of the story of evolution. (I have wondered whether the person who did the opening sequence for Big Bang Theory saw that show). Some of the projectors melted during the show—we left a few things melted down. That event was another highpoint.

Figure 10. Moon Bowl Poster. Note bottom right, Lights by Spontinuity. Art by Bill Hess.

Then in 1970 came marriage and home life, and I had to suspend my lightshow. The late nights and party life had been too much. I had helped set up the Mammoth Gardens project in Denver, where a rich young dude bought an old roller skating rink and set up a club. We were hired to do the lighting, which mostly consisted of stage lighting, not much lightshow per se. I did lights for Joe Cocker, Mad Dogs and Englishmen, Jethro Tull, The Who and more. I moved on and became a furniture designer and maker.

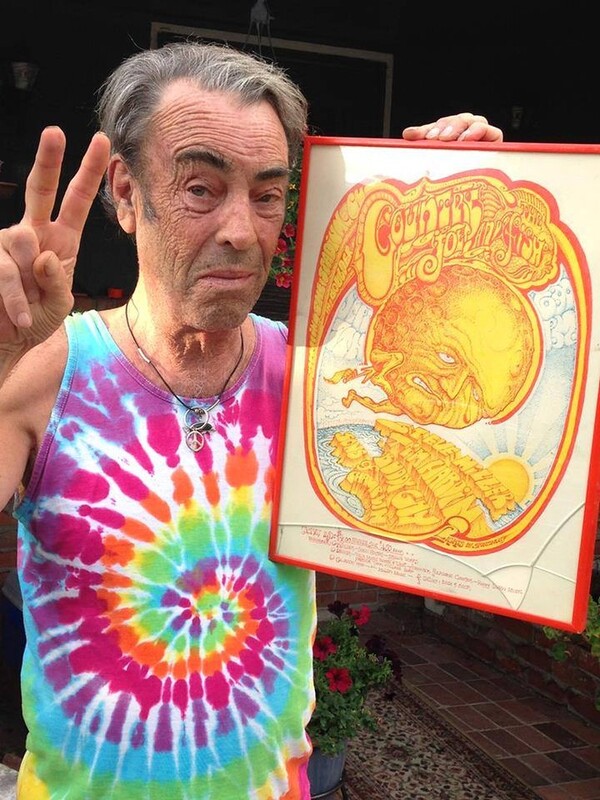

Herbie kept Spontinuity alive for a while, doing lights for local events in Colorado until his life as a gold miner led elsewhere.

Figure 11. Herbie Hendricks at 72, Master of the Overhead Projector. Courtesy of Herbie Hendricks.

I had moved to Australia by the time the world of digital projection arrived in the early 2000s. I fell in love with the possibilities, and once again set out on the lightshow journey. I renamed my new company Dream Seeds.

Digital imagery has such purity of colours, clarity of images and built-in animations that are fun to play with, but I will always insist that merging and shifting images through one’s fingers over the lens has more nuance, art and organic beauty than any computer will ever achieve.

Dream Seeds has performed at numerous festivals in Australia and the US (Joyfest, Harmony Fest, Byron Bay Peace Festival, Oregon Country Faire, She Shamans) as well as concerts, weddings, parties and lectures.

Figure 12. Lightshow for a wedding, 2021, Sunshine Coast, Australia.

In ’02, ’03 and ‘04, I was hired to be “the lighting guy” for a series of three Wesak Festivals, a New Age version of Buddha’s birthday celebrations, in Brisbane, at Uluru and in Sydney. I provided backdrop visuals for each speaker, having only hours to interview them, find or create images and graphics and get it on screen behind them.I still own the glass dishes (large clear clock faces in different sizes) and some other effects gear for the full light shows I will, one day, perform again. I have projectors, thousands of slides, plus many thousands of created and curated images on my hard drives, and I can do a lightshow at the drop of an Elf hat.

My work as a light artist in recent years has involved much travel. Between 2005 and 2017, I travelled around the world as a storyteller to places including Sydney, Melbourne, Byron Bay, Brisbane, Mumbai, New Delhi, Bruges, Miami, Asheville, Houston, Santa Fe, Boulder, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Malibu, Cancun, Isla Mujeres and Hawaii. I carried a projector and laptop, doing lightshow/lecture/workshops and presenting an illustrated contemporary neo-myth called the “Legend of the Golden Dolphin”, hundreds of times. That’s a topic for another place. The medium holds so many possibilities.

Figure 13. From the Legend of The Golden Dolphin.

I watched the “classic” lightshow that used liquids, images and light manipulation blossom in the ’60s then fade away. It did not take long for them to virtually disappear. By the mid-70s the shows were mostly memories. Programmed stage lighting and fancy machines to spin lights and change colours had moved in. And then came lasers.

While fascinating for a short while, for me (and I have learned that other lightshow artists agree) lasers are quite limited, and are soulless flickers of curious light and patterns without the organic mystery of photographs, film and most certainly liquids.

Liquid projections can be just sloshing around with colours. When done by masterful artists they can be astonishingly creative. A lightshow I saw with Timothy Leary’s lecture in Santa Monica in 1969 was truly magical, using the most basic equipment to weave living rainbows that wrapped and warped the room. Masters of the lumia technique, their shows consisted of rainbow light only, working with light itself, as bent and shaped by liquids, wave machines, lenses and mirrors. I wish I knew who they were.

Figure 14. Mixed image: wet web, frog, flower, mandala and mystical figures.

Most concert lighting performances now consist of preprogrammed materials with little live, analog, hands-on creation. The projection of liquids has found a small resurgence and lumia has become more common than it used to be. These days a few artists are using cameras linked to digital projectors to capture imagery of liquids or other media on flat panels of LEDs.[1]

I am acutely aware that, to see a flowing stream of faces morphing into flowers, into waves, into the intent gaze of a Buddha, into a Fibonacci spiral of sunflower seeds, into a film clip of a small mountain creek glistening in sunlight, is to be presented with inspirations for personal discovery and reflection.

Figure 15. The Path leads to wisdom.

On a dance floor I experience images as brief glimpses upon which to reflect. Among the minds of people who are high, ideas can be enhanced, highlighted, made more available. There, one can experience the glory in a child’s smile or feel the “delicious grace of moving one’s hand”, as Leary put it.

Figure 16. Welcome to the Gate of Future Dreams.

To support happy, dancing people by shining a light on beauty is a kind of social service. It has been an act of service that I have been fortunate to offer over my years in the dark, usually unseen and often unacknowledged, surrounded by people in joyous communion with themselves and their companions. For me, it has always been a kind of ritual, an event in which artists are empowered to flood the sensory experience of a willing congregation with sound, colour and light, to enhance ecstatic communion.

It is a great pleasure to “shine a light” so that others may find Joy.

An American ex-pat living in Australia since 1999, I have enjoyed various kinds of employment. In the US, I was a furniture designer and builder, a founder of several independent schools, a teacher of Permaculture, an independent researcher on interspecies communication, a workshop leader and a storyteller. In Australia, I have authored a book on dolphins, earned two degrees, taught at Universities, written and presented a TV special, led a wellness program at a dolphin rescue facility, become a beekeeper and been a storyteller. All along, I have done lightshows and worked with light as an art form and means of service.

[1] See Psychedelic Lightshow Preservation Society on Facebook.