Figure 1. Still from the video “Rabisca o chão” (Imperadores da Dança 2019).

Passinho Chronicles: Unveiling Urban Narratives Through Dance

University of Barcelona (Spain)

<http://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2024.16.01.11>

The article discusses how choreography and music produced in the favelas (“marginalized neighbourhoods”) of Brazil may be approached simultaneously as a political practice and as a narrative which performatively reconfigures dystopian urban scenarios. The music videos “Rabisca o chão” and “Notorius 150” serve as a backdrop to guide us through the social conjuncture in which funk is inserted.[1] This includes funk as a music produced in the favelas; the passinho dance style funk gave birth to; the socio-spatial context of the favela; the black body as the centre of the narrative and the television news footage representing the war on drugs. Ultimately, this article highlights how artistic expression lays the groundwork for forging a new identity for black communities in Brazil by demonstrating the political potential inherent in dancing.

In 2019 between clicks on YouTube and attempts at dancing in my living room, I came across a video which caught my attention for presenting funk carioca (“funk from Rio de Janeiro”) as an urban chronicle. The music video “Rabisca o chão” shows a dance performance created and envisioned by the group Imperadores da dança (“emperors of dance”) from the favela of Jacaré in the north of Rio de Janeiro.

Music video “Rabisca o chão” by Imperadores da Dança (2019).

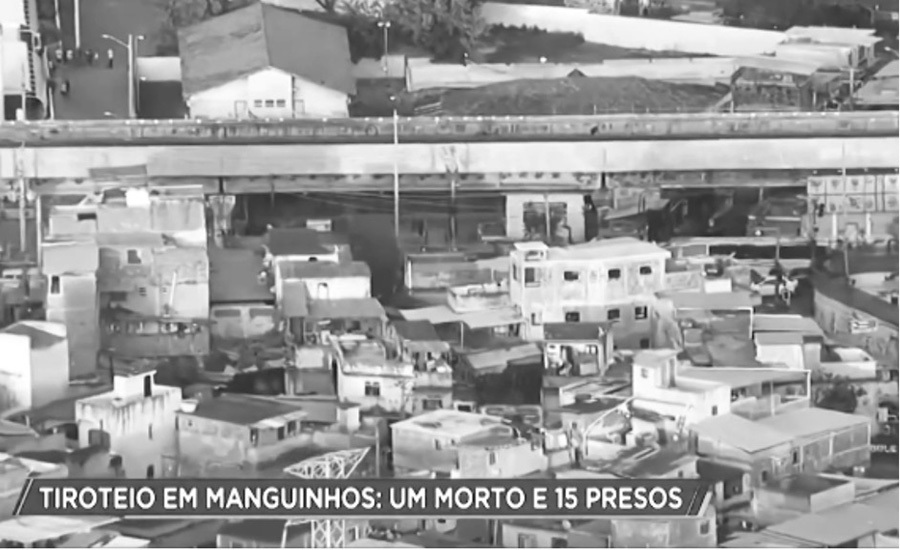

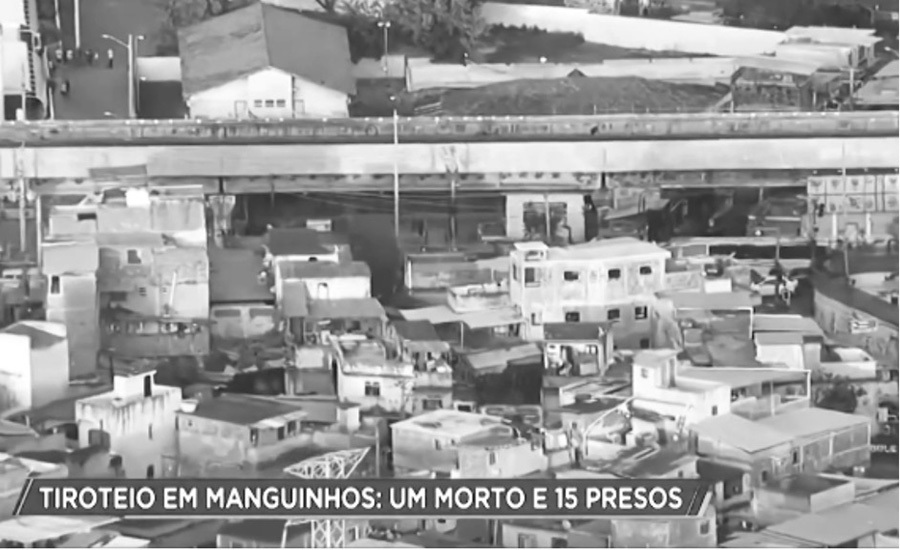

The clip is a dance production presenting two (coexisting) realities. First, there is the media representation of the favela and what is often portrayed as the war on drugs. At the beginning of the music video, we watch black and white images of police clashes made by news from an aerial or distant perspective. The sounds of gunshots and shifts to images of military intervention are followed by a poem called Rei da balística (“King of Ballistics”) by Severo Idd:

Pow pow pow!!! Got scared big boss?

No warning is given when the firing starts!

First law of the favela huh:

Always walk prepared

To never be caught off guard

Bang Bang

Another body lying on the ground

You don't even need to be a psychic

The media will say it was a thief

I guess a lot of doctors are being hired

Every week there’s an operation

Pow pow pow pow pow

Today it’s like New Year's Eve

Pow!

Gun

Bang!

Rifle

Boom!

Grenade

Trrrr…

Glock in burst

Twenty-eight years of listening to this every day

Fuck! Call me king of ballistics

The day has dawned

Sunday

I'm going to the street market to buy my pastry with sugarcane juice

Shiiiiii, they broke down my door. Fuck!

I guess it was the cops…

Who has nothing to hide has nothing to fear?

Go for it you’ll see!

The worst thing about this world is paying without obligation.

I thought that to break into the house of others would need a mandate

On asphalt it’s one thing

In the favela they hit first and

ask questions later

Hesitate and you’ll see!

If you are not going to end up all broken.[2]

This poem is recited alongside black and white news footage, in which crime and violence are highlighted (Fig. 1). When the funk beat kicks in, the images gain colour and the media footage is replaced by a group of boys (the Imperadores da Dança) entering the shot by dancing passinho, a dance style originating from the funk carioca of Rio de Janeiro (Fig. 2). The dancers reintroduce us to the same neighbourhood which had just been portrayed through media footage, but this time from a ground-level perspective. As they move through the streets, others join them in dance movements. The linear path of their dancing through the alleyways fosters a sense that we are all walking together. It is as if a new territorial map has emerged.

Figure 1. Still from the video “Rabisca o chão” (Imperadores da Dança 2019).

Figure 2. Still from the video “Rabisca o chão” (Imperadores da Dança 2019).

While there are basic passinho moves, there are no rules to demarcate what is “correct” or “incorrect”. This gives dancers the freedom to interpret moves in various ways, and personal adaptations can evolve into distinctive styles. The goal of the dancer is not to imitate but to reinvent. It is the cultural background of the dancers that is largely responsible for giving this improvisation the hybrid aesthetic tone of passinho.[3] This playful competition serves as the driving creative force behind the continuous evolution of this dance style.

The improvisational aspect of the dance creates an idea of being in a different space in the music video “Rabisca o chão”. In contrast to the first presented images of a dystopic reality in the favela, the choreography presents a new spatial relationship. While dancing, the dancer is no longer part of the confrontation presented at the beginning of the video. In this sense, the dance moves contemplate a different reality, in which unfamiliar spaces are presented as familiar.

Favelas are considered to be one of the faces of the black diaspora in Brazil. Although each favela has a specific history of emergence, it can generally be said these urban areas descend from a long history of a lack of public policies for the inclusion of poor and black people in the country. Therefore, carioca funk is a cultural manifestation representing these historical, social and geographical origins. In the same way passinho is also deeply connected with issues linked to the favelas and broader Brazilian reality. Such a reality can be seen in “Rabisca o chão” when the state's narrative is placed alongside the narrative of the favela residents, the dancers.

While funk carioca has earned its place as a musical genre within Brazilian culture, the art emanating from this cultural framework mirrors the lived experiences of its community, offering a profound representation of life and permeating it with fresh perspectives and meanings. Funk, along with other cultural expressions originating in marginalized neighbourhoods of Brazil, has played a significant role in shaping an identity rooted in local aesthetics. This cultural movement serves as a form of urban narrative, telling stories and experiences of these communities.

Since the 1990s, when funk carioca transcended the limits of Rio's favelas and started being played on the “asphalt” of wealthier neighbourhoods, it has evolved into one of the largest cultural mass phenomena in Brazil.[4] This widespread popularity has led to heterogeneous movements that encompass countless rhythms, themes and expressions. To name a few subgenres, there are 150 bpm, bregafunk, proibidão, funk melody, trapfunk, funk ostentação, charme and many others.[5] Its popularity is directly related to the fact that this cultural movement incorporates the lifestyles and experiences of Brazilian youth, especially those living in favelas. Funk carioca and its subgenres constantly renew themselves, bringing to the lyrics of the songs and the movement of the dance bodies aspects of its territoriality.

Electronic musicality, blended with atabaques (“drums”), gives funk an unmistakable vibe.[6] However, since its emergence, dance has played a central role in this genre, forming a kind of seam between parties and songs. Thus, among its diverse characteristics, funk is fundamentally electronic dance music.[7] That is, the sound is not only heard passively by the ears, but also felt throughout the body, activated by the beats. In Brazil’s black electronic musicality, countless songs discuss the impact of low-, medium- and high-frequency technology on the body (Albuquerque 2023). This makes the dancing body a revealing element of funk.

Thinking about what dance can do politically, in 2020, I came across another music video that explored this relationship between passinho, funk and territories.

Music video “Noturno 150” by Heavy Baile (2020).

“Noturno 150” is a production by multimedia funk collective Heavy Baile, in which the dancer (Ronald Sheick) choreographically infiltrates the paintings of master painters of the Western tradition held in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art in New York. While Degas painted classical ballerinas, Heavy Baile brings masterful Brazilian passinho to break down the European aesthetics (Fig. 3). The dancer crosses spaces that the black body supposedly does not occupy.

Figure 3. Still from the video “Noturno 150” (Heavy Baile 2020).

This reinforces the notion that dance in the favelas also emerges as an artistic way of life. The narrative of both music videos explores the possibility of fostering an alternative form of urban and social mobility through fast and vigorous dance movements. In seemingly unsuitable terrains for dancing, the dancers lay the groundwork for cultivating a new identity for communities residing in Brazilian favelas.

The dancing bodies and narratives presented in both music videos are elements that allow us to investigate the process of territorialisation of the passinho dance from the dimension of the dancer's body (here thought of as territory), reaching the space where they dance (physically and socially) and beyond (media representations, for example). The fundamental question is how can an urban and contemporary dance create new spaces within its own territory?

The possibilities of navigating through different locations constitute the urban rhythm, a dynamic that resembles a kind of a dance. In other words, the urban dynamics functions as a dance, as physical movement interacts with urban elements such as traffic lights, sidewalks and pathways. Consequently, daily commutes establish a system of flows within the city, continually shaping and reshaping the spaces. Thus, the built environment confines movement and establishes rhythms like a conductor in front of an orchestra. Nonetheless, it is not only physical elements that determine the urban choreography of everyday life.

Consider, for example, the iconic scene from “Singin' in the Rain” (Kelly et al. 1952), where the actor Gene Kelly dances in rain. In his joy, the character jumps and spins into and out of space. The dance itself seems endless, until Kelly is interrupted by a police officer who stops the dance by simply appearing in the scene, stopping, and crossing his arms. The police, in other words, choreograph the scene—much like they choreograph the first part of the music video “Rabisca o chão”. This perception underscores that the police is a tangible construction that is comparable to architecture (Lepecki 2011). Their primary role is to ensure the reproduction and preservation of predetermined patterns of individual and collective movement. This combination of elements allows us to understand urban space as a choreography orchestrated by different elements present, or not, in the same space.

These human dynamics between the body and space shape the urban environment. Urban space permeated by ephemeral movements characterizes everyday life. Consequently, bodies not only form a society with other bodies but with all other mobile and immobile elements of the context in which we find ourselves daily. This demonstrates how the city is primarily shaped by an experience and perception that is always corporal.

In this context, we can understand passinho as a series of rehearsals in which the dancer experiences space with the body. They do this by placing themselves at the centre of the narrative and speculating on other ways to occupy the streets where they live. Dance movements bring an imagination that presents itself in the form of a freedom: to be able to walk without having to be “always prepared”, as expressed in the poem of Severo Idd quoted above.

This aspect is further emphasised by the fact that these productions primarily take place in public spaces such as squares, streets, cultural centres and bars. It is not an art form that removes young people from the streets; rather, it positions them within the public sphere, right at the epicentre of the struggle for the right to the city.

The "street bodies" that dance at balls, in museums and alleys, do more than challenge the attempts at discipline and control over bodily actions that are imposed on them by society. The lack of discipline and non-docility—in the sense used by Foucault (1995)—of these bodies provokes a sensitive signal of the possibility of a physical existence outside normative patterns. After all, the most important thing we learn from Foucault is that the living body is the central object of all politics. There is no politics that is not body politics (Preciado 2020).

The dancers in the video examples discussed in this article are dancing in the streets and inside paintings, in the process inscribing these spaces with their bodies. Through passinho, we can reflect on the capacity of corporeal material to challenge the stereotypical perceptions of the city's territories. The dancing body is capable of shifting the perception of space from place to affection, being able to cognitively modify the way in which a certain group in a given historical time perceives and signifies space. In this way, dance can be understood as a type of body knowledge constructed and sedimented simultaneously as it is experienced.

Passinho, while not explicitly aligned with any particular cause or intended as a form of political activism, can be regarded as a cultural expression that transcends the boundaries of everyday life, assuming unforeseen social roles (e.g., steering young individuals away from drug trafficking, serving as a strategy for social interaction and fostering aspirations to pursue a professional artistic career). Such roles can directly impact the local daily life in which this youthful expression originates.

This urban and contemporary dance, which mixes several references translated into vivid movements, ends up becoming a significant element of the body's intervention in the social territory that regulates and controls it. However, the performance is not presented as a direct alternative to the historical violence that permeates the reality of those who live in the favela. Instead, the dancer openly exposes this reality. In this manner, young people who embrace passinho can take control of their own representation, even though we know that this process involves different interests on the part of mainstream media, the state and the consumer market.

The music videos “Rabisca o Chão” and “Noturno 150” offer several perspectives in discussing this complexity. This includes music produced in the favelas; the dance style of passinho, created from funk, hip hop and other Brazilian (or not) references within the favelas; the socio-spatial context of the favela; the black body as the centre of the narrative and finally, the representation of the favelas from outside by television news footage showing the war on drugs and police interventions.

Returning to the beginning of the text, when I first watched these two music videos, I felt like the dancers were inviting me to take a walk through the city. These elements reveal how both the music video and the choreography function as tools of political agency. In this case, the dancer negotiates space, whether it be the symbolic space of grand art galleries (and power), or the simple right to walk freely through the streets of their own city.

Despite the engaging power of the passinho, it is evident that it cannot fully dismantle a longstanding and defining history of segregation and stigma. Nevertheless, this dance style emerges as an alternative that challenges the boundaries of the (normative) narrative constructions. Ultimately, these videos reveal how the performative act of dancing in these contested spaces rewrites the story of the favela, forging new collective identities for black communities in Brazil.

Natalia Figueredo is an architect, urbanist and cultural theorist from the Brazilian Amazonia, engaged actively as a member of the Observatory of Anthropology of Urban Conflicts (OACU) and contributes to the training platform Antiarq. Presently pursuing a PhD in culture and society at the University of Barcelona, her research delves into informal urbanism within the Amazonian urban territory. Moreover, Natalia collaborates with Sonic Street Technology, a project at Goldsmiths, University of London, focusing on music technologies in urban Amazonia.

Albuquerque, GG. 2023. “Cientistas do grave: o som afroeletrônico”. Volume Morto, 28 August: <https://volumemorto.com.br/cientistas-do-grave/>, (Accessed 17 September 2024).

Britto, Fabiana, Jacques Dultra and Paola Berenstein. 2008. “Cenografias e Corpografias Urbanas: Um Diálogo Sobre as Relações entre Corpo e Cidade”. Cadernos PPGAU/ UFBA n. 6: p. 79-86.

Fernandes, C. S., de Oliveira, H. S., & Barroso, F. M. 2021. “Os Relíquias do Passinho: Táticas e Performances do Corpo que Dança”. Esferas, 19, 44–53. <https://doi.org/10.31501/esf.v0i19.12367>.

Foucault, Michel. 1991. “Docile Bodies”. In Discipline and Punish. New York: Vintage Books:<https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/jhp026>.

Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press.

Henriques, J. 2021. “Street Systems and Knowledge Systems [sst research 2.0]”. Sonic Street Technology. Posted 4 October 2021: <https://sonic-street-technologies.com/Sst-Research-2-0-Street-Technologies-and-Knowledge/>, (accessed 17 September 2024).

Lepecki, A. (2011). “Coreo-política e Coreo-polícia”. Ilha Revista de Antropologia, 13(1,2). <https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-8034.2011v13n1-2p41>.

Nascimento, L. M. P. do. (2017). No Território do Passinho: Transculturalidade e Ressignificação dos Corpos que Dançam nos Eespaços Periféricos [Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo]. <https://repositorio.ufes.br/items/b28d9538-aab9-4746-93c4-6c9348129209>, (accessed 17 September 2024).

Preciado, Paul B. 2020. “Learning from the Virus”. Artforum: <https://www.artforum.com/features/learning-from-the-virus-247388/>, (accessed 17 September 2024).

Sá, S. P. de. 2007. “Funk Carioca: Música Eletrônica Popular Brasileira?!”. E-Compós, 10(0). <https://doi.org/10.30962/ec.195>.

Sá, S. P. de. 2003. Música eletrônica e Tecnologia: Reconfigurando a Discotecagem. Recife: Anais do XII COMPÓS.

Sovik, Liv and Brian D'Aquino (2022). "The Power to Name and Other Dilemmas Presented by Brazilian Funk Subgenres". Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music and Culture 14 (1). <https://doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2022.14.01.10>.

Branco, Renée Castelo. 2013. Da Cabeça aos Pés. Brazil:

GloboNews Documentário.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_mYAZqQ55qg>.

Donen, Stanley and Gene Kelly. 1952. Singin’ In the Rain.

USA: MGM.

<https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0045152/>.

Heavy Baile. Noturno 15. YouTube, 2:50. Uploaded on 2 September 2020.

<https://youtu.be/U4hvMF_LKWM?si=gJn_O-b5L1Zl1CwH>

(accessed 17 September 2024).

Imperadores da Dança. Rabisca o chão. YouTube, 7:01. Uploaded on 20

November 2019.

<https://youtu.be/knFRzpUIwzk?si=mV0XB8qHAN414DNR>

(accessed 17 September 2024).

[1] For a discussion of the funk genre and subgenres see Sovik and D'Aquino (2022).

[2] This poem has been translated by the author. Here is a transcription by the author in the original language of Brazilian Portuguese:

Pa pum pum!!! Ficou assustado chefão?

Quando a bala come não tem aviso prévio! Primeira lei da favela hein:

Ande sempre preparado

Pra nunca ser pego de surpresa

Pá pum

Mais um corpo estirado no chão

Não precisa nem ser vidente

A mídia vai falar que era ladrão

Acho que tão contratando médico demais Toda semana tem operação

Pá pum pum pum pum

Hoje tá pique Reveillon

Pá

Pistola

Pum

Fuzil

Bum

Granada

Trrrr...

Glock em rajada

Vinte e oito anos escutando isso todo dia Porra! Pode me chamar de rei da balística

O dia amanheceu

Domingão

Vou na feira comprar meu pastel com

caldo de cana

Xiiiiii, arrombaram minha porta. Fudeu. Acho que foram os canas...

Quem não deve não teme?

Vai nessa pra tu ver!

A pior coisa desse mundo é pagar sem

dever.

Eu pensei que pra invadir a casa dos outros precisaria de um mandato

No asfalto é uma coisa

[3] Passinho is not the only style of dancing funk carioca. At the same funk party there would be several types of dances, and relationships to gender characteristics and sexual orientation are great indicators of the ways to move the body to the sound of funk. See more in Renée Castelo Branco’s (2013) documentary “Da Cabeça aos Pés”.

[4]Do morro pro asfalto ("From the hill to the asphalt") is a colloquial expression typically used in Rio de Janeiro to mark the social difference between the middle-class neighbourhoods (asphalt) and the favelas (hill). It is an expression that connotes the social and racial inequality that permeates Brazilian cities, a deep socio-economic division which the journalist Zuenir Ventura (1994) called "cidade partida" (“cracked city”).

[5]Funk carioca has had different influences and went through several stages. The first phase was its emergence in the Favelas of Rio de Janeiro in the late 1970s, influenced by the sound of Miami Bass. DJ's played only music in English at parties, which was mainly marked by the beat of the electronic drum in the song Planet Rock produced by Afrika Bambaataa. The second was the development of the Rio style, with Brazilian lyrics and production, highlighting the work of DJ Marlboro. Finally, the third is the recent popularisation of the genre in Brazil as well as in the universe of electronic music lovers (Sá 2007).

[6] Due to its influence, it is common in Brazil to refer to carioca funk and its subgenres simply as funk.

[7] This means that funk is dancing music played by DJs for audiences in open spaces (bailes) or closed spaces (clubs), and its chronological cut dates back to the late 80s (see Sá 2003).