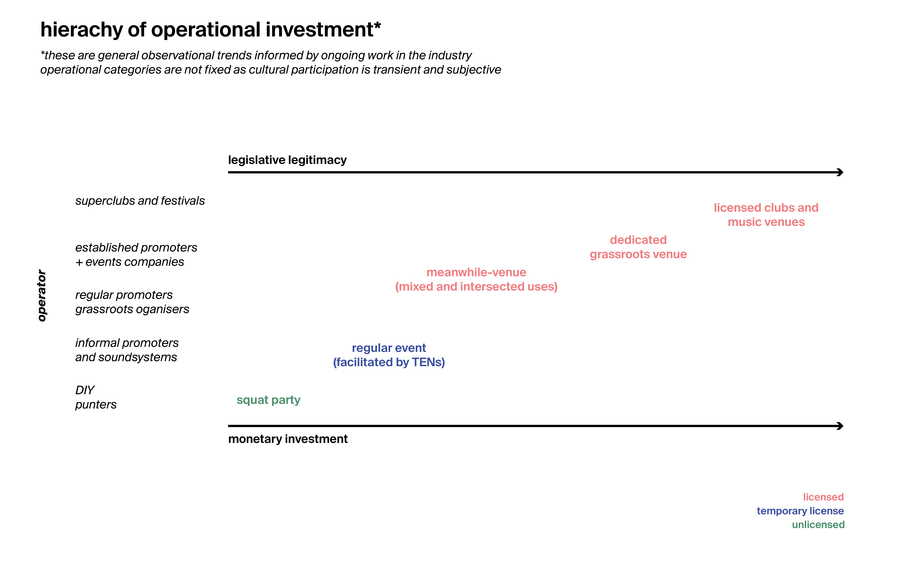

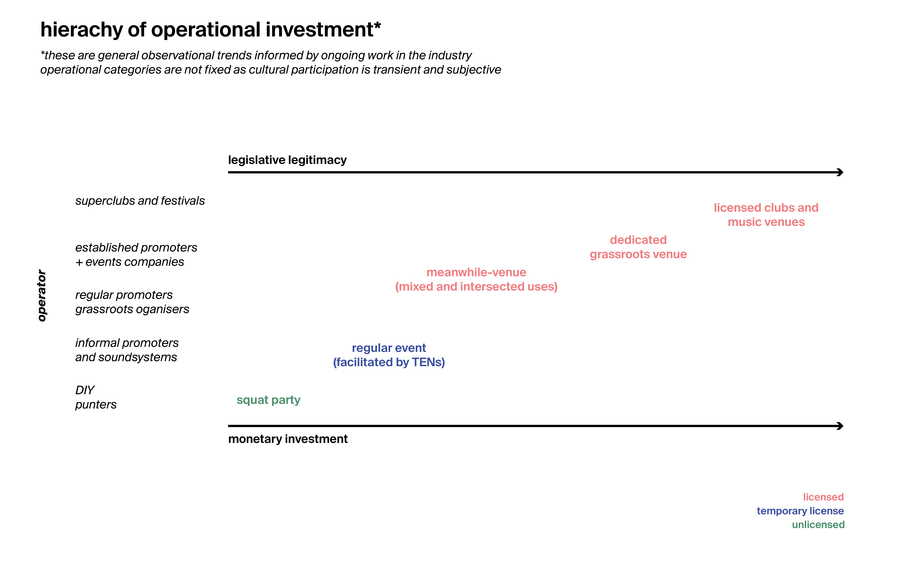

Figure 1. Diagram to describe the “Hierarchies of Operational Investment” required to establish different types of music and party venues. Ella Adu, 2023.

Reflections from the Frontlines of Grassroots Venue Design

University of the Arts London (UK)

<http://dx.doi.org/10.12801/1947-5403.2024.16.01.08>

Do good parties need good buildings? Histories of DIY music culture in Britain would suggest they don’t. Arguably, the co-dependence between architecture and real-estate positions the architect as an antagonist to the propagation of grassroots venues in British cities. Nonetheless, it’s essential for small venues to negotiate the established structures of urban governance to access civil resources in the long term: public safety, funding and spatial security. Free parties are fun, but the future of DIY venues should not be relegated to a state of universal precarity.

In the UK, the existing legislation that manages the built environment is incompatible with DIY methodologies. This article explores how architectural practice can be adapted to work in solidarity with grassroots operators and, in doing so, subvert and contest dominant modes of building production. Two case-studies are used to illustrate these complexities. The specific and situated architectural methods and case studies described in this article refer to work by Beep Studio, an architectural practice based in South East London, with specialist experience in grassroots typologies. Beep Studio founder and director Ed Holloway describes his practice as follows:

I created Beep Studio in 2011 with a core focus on regenerative design as a mode of operating in a rich ecology of community led groups. One of my main interests is to develop collaborative and symbiotic relationships that increase access to, as well as celebrate grassroots culture. Some of the more recent community led projects Beep Studio have supported are very much a ground up process, with many up against barriers with leases, council bureaucracy or lack of funds, and are often fighting to secure their place as a cultural and community led organisation. Beep Studio members enjoy participatory roles, nurturing community clients to develop accessible cultural spaces.[1]

This exploration defines a new music venue as that which has been created where previously one did not exist, highlighting the unique challenges in trying to replenish the rapidly diminishing stock of London’s DIY venues. This is because there is significant difference between reoccupying a site with a pre-existing licence for amplified music, versus transforming a previously unlicenced site into a licensed venue with the requisite designations.

To fully recognise the ordeal faced by those working to open new music venues, conventional methods of planning, designing and constructing buildings should be understood.

In the UK, the built environment is produced through a set of design processes and bureaucratic functions: specifically planning, licensing and building regulations. These statutory processes are underpinned by carceral laws which protect the interests of private property ownership. There are various ways to make buildings, but the majority are designed, built and exchanged according to a fixed a programme of delivery: the RIBA Plan of Work, which self-describes as ‘the definitive model for the design and construction process of buildings’ in Britain.

Within this context, an architect takes on the role of Project Lead, responsible for the design and specification of the build, in addition to overseeing the construction process and subsequent handover of the building to its intended operator. The architect is the primary mediator between all stakeholders of the building: landowners, Responsible Authorities, technical consultants and engineers, tradespeople, contractors, volunteers, trustees, promoters, punters and venue operators. All workers contributing to the development of the brief, design and construction of a building have their work allocated through protocols of contracting, bidding and tendering.

In Britain, grassroots music venues are being eradicated by a set of interlocked hostilities: the covid-19 pandemic, speculative residential development, increased business rates and 13 years of austerity among them (O'Connor 2023). These material transformations are facilitated by a rightward shift in the broader political sphere, entrenching regressive attitudes across all levels of spatial legislation.

Built environment regulations in the UK are at once oppressively pedantic and wantonly disordered. Some sectors (offices) enjoy the freedoms associated with ongoing deregulation of planning permissions whilst others, (licensed venues) undergo intensified scrutiny (see for example Licensing Sub-Committee 2022 and Kollewe 2023). Traversing these administrative minefields to permit, license and construct a new music venue poses an existential risk to the grassroots operator. Professional fees associated with meeting statutory requirements pose a financial risk, which must be calibrated with the operational risk should the planning, licensing or building control application be denied. Once opened, a venue can still be subject to statutory disciplining in the form of an enforcement, should the operation fail to meet the conditions described in the initial application.

Similarly, an architect’s own professional habitus internalises regressive neoliberal frameworks. The profession is deeply hierarchical sexist, elitist and ununionized, contributing to top-down modes of production (see Hill 2019, UCL 2022 and RIBA 2023). Willingly or not, the traditional architect is often complicit in the reproduction of unequal property relations which stifle grassroots potential.

Figure 1. Diagram to describe the “Hierarchies of Operational Investment” required to establish different types of music and party venues. Ella Adu, 2023.

Meanwhile-use arrangements can offer a regularised alternative to squats or ad-hoc Temporary Event Notices (see fig.1).[2] Both case studies presented in this exploration are examples of meanwhile-use lease and license agreements. A 2020 report commissioned by the Greater London Authority (GLA) defines meanwhile-use as:

a situation where a site is utilised for a duration of time before it is turned into a more permanent end state, taking advantage of a short window of opportunity. Meanwhile interventions are tactical and slot into wider strategies of planned change… . (ARUP 2020: 14)

“Wider strategies of planned change” highlights the use of meanwhile-tenancies as a subprocess of regeneration (Arup 2020). The sites in question are often derelict and will be located within a larger regeneration masterplan under the ordinance of a dedicated council department, or a QUANGO often in partnership with a private developer.[3] When evaluating statutory applications, the Regeneration department is legally separated from the Planning department, whose spatial policies and ambitions may or may not be aligned. This division of responsibility within the council is exacerbated by sustained under-funding, resulting in contradictory advice, protracted meetings and even refusal of statutory permissions. Refusals can occur despite internal support from other council departments such as business development, regeneration and culture.

Nonetheless, meanwhile-use occupancies offer affordable and relatively sustainable modes of building re-use by reappropriating existing spatial typologies to revive degraded cultural and social infrastructures. Often, grassroots operators deploy mixed-use programmes where daytime activities—community gardens, cafés or meeting spaces—supplement licensable night-time activities—amplified music, performance or comedy events—thereby maximising opportunities for revenue generation.

Meanwhile-use programmes intensify both the occupancy and the usage of buildings they inhabit. In the context of local planning policies, these diversified uses might be seen to conflict with the strategic aims of a Local Plan. In granting said programmes with the necessary Planning or Licensing permissions, councils may deviate from established policies on a discretionary, case-by-case basis, exposing them to some legislative risk.

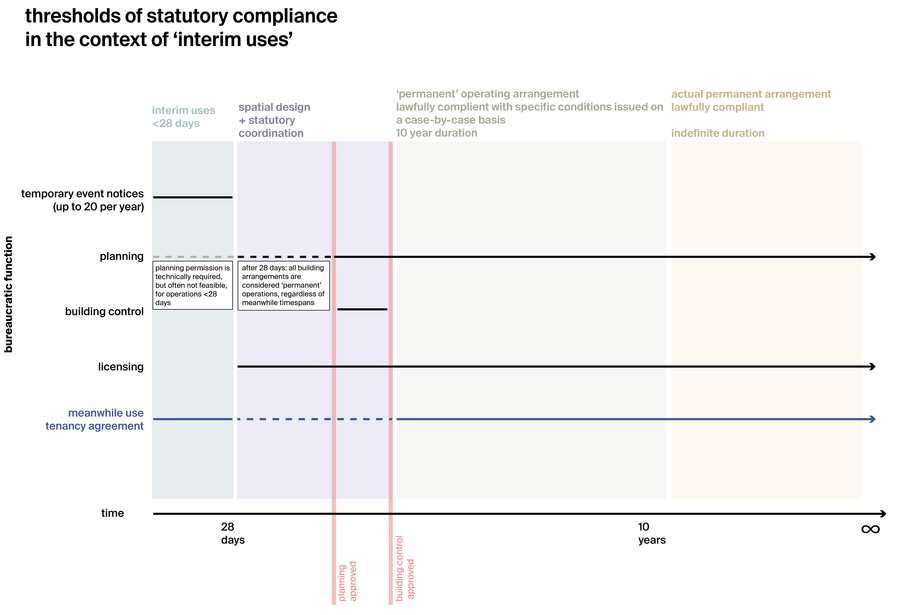

Diversifying building usage can provoke a frustrating paradox: grassroots operators rely on the revenue generated by day-to-night occupancy models to meet the costs of developing the necessary built infrastructure, business operations, staff wages and other overheads, within a lease period that could end abruptly if the surrounding regeneration programme is accelerated. Yet, these multi-use models themselves generate legislative risk to the council, exacerbating the potential for statutory enforcements or refusals, particularly if the meanwhile occupancy is longer than 2 years, tending towards “permanence” (see fig.2). Interfacing with local authorities subjects operators to slow and complex matrixes of bureaucratic decision-making, which consumes already limited temporal and financial resources.

Existing protocols of spatial governance struggle to accommodate the occupancy models needed to support grassroots inhabitation. Even in meanwhile-use arrangements, there is some cynicism in deploying grassroots organisations to oversee the planned obsolescence of unwanted sites. Grassroots operators are tasked with the material and programmatic rehabilitation of the site, without invitation to partake in long-term visions of prosperity or tenure security once the wider redevelopment is complete. The RIBA Plan of Work is aligned with macro legislative frameworks designed to regulate built spaces which are permanent. It does not easily integrate with time-sensitive DIY methods, which prioritise collective practice, experimentation and iteration through trial and error. These conditions pose an extraordinary waste of the social equity generated from DIY innovation.

However, the current paradigm is not inevitable and (with perseverance) can be transformed. Grassroots venues can conform to, or subvert, established structures of urban governance relating to planning, environmental health, building regulations and licensing. New typologies of architectural practice can emerge from these struggles.

Figure 2. Diagram to describe the statutory milestones needed to comply with UK planning and building legislation, and how these intersect with meanwhile-use arrangements. Ella Adu, 2023.[4]

An architect working on music venues might be routinely asked about acoustic design optimisation. Yet, the ongoing degradation to DIY music culture cannot be remediated through the design process alone.

In the built environment, sound propagation is regulated through design (planning), but usually enforced through frameworks of safety and public order (licensing). Therefore, the music emitted from music venues must be controlled operationally, through the management, or mitigation, of behaviours associated with sound including: the hours at which sound is being emitted, the volume of sound and the sound of those leaving the venue. Sound (impacting others) is perceived as noise and consequently managed as “nuisance”.

Subsequently, the construction of music venues becomes an explicitly political venture involving careful negotiation with Responsible Authorities—including licensing officers, environmental health, the police and elected members—alongside sensitive consultation with neighbouring communities, to build a positive consensus toward the proposed venue. Applying technocratic or design-based solutions in isolation of applied political coordination can be explicitly harmful to the operator and surrounding communities.

Moreover, achieving statutory compliance requires a level of bureaucratic literacy beyond the scope of most grassroots operators. Architects are essential for various kinds of administrative synthesis: scouring local plans to identify legislation which safeguards local culture, summarising a planning officer’s report, advocation in a Licensing Sub-Committee hearing or writing letters of appeal, among other examples. To negotiate these conditions, the grassroots venue designer must go beyond conventional parameters of architectural thinking and commit to a more holistic role, working as an ally, advocate and pragmatic administrator.

In these instances, design takes on many forms. It can be carefully designed conversations with a Regeneration Project Lead at a Local Authority QUANGO who is either unaware, or unmoved, by the fact that they hold the venue’s future under total subordination. Or it may be the design of an iterative decision-making process to help grassroots operators clarify their interests and incorporate requests from community investors.

This holistic role is made possible by the grassroots architect’s personal investment in the DIY scene outside the confines of waged work: “as an ordinary punter”, as studio director Ed Holloway describes. This dual experience, as both organiser and reveller, affords the architect uniquely situated knowledge that encompasses networks of friendship, resources and methodologies which circulate through the DIY scene. These contexts enable the designer to platform modes of tacit knowledge which are otherwise ignored by conventional orthodoxies of spatial production.

The role of the architect and the bureaucratic difficulties facing DIY operators is best understood through example. The following case studies demonstrate the complexities of building new grassroots venues in London.

Grow Tottenham was a mixed-use scheme, including events spaces, which ran from 2018-2022.[5] Located in a former warehouse in Tottenham, the site was secured from a housing association landlord under a 1-year rolling Licence to Occupy prior to commercial development. The meanwhile-use tenancy was organised through a third-party regeneration company, who implemented sub-licence arrangements for grassroots operators. The site contained three warehouse units, two of which were operated by a nightclub (referred to as Operator A). The other warehouse, alongside a large external area, was operated by Grow London CIC (referred to as Operator B).

As a one-year rolling occupancy, the site was technically subjected to the same statutory measures as longer or permanent tenures. However, the realistic timescales needed to obtain development permissions through planning would mean that the tenant operations might be expired before such permissions could be granted (see fig. 2). Both operators (A and B) implemented a variety of uses which would not otherwise be regularly permitted in the context of residential and commercial redevelopment, illustrating how meanwhile-use frameworks can support diverse building uses.

The architects worked with Grow (Operator B) to renovate the site under a light-touch provision of design services. Considering the building’s limited lifespan, key spatial interventions—accessibility, fire-plan arrangements and noise-control measures—were installed by trade professionals, with some assistance from community volunteers. These interventions supported various community uses: an event space, studios, a café and bar and extensive hard-standing garden, followed by a greenhouse and further garden infrastructure (Time Out 2019). The interventions were successfully iterated over time and in response to the community’s evolving needs.

A local stakeholder captures the unique and transformative spatial dynamics of Grow Tottenham very effectively.

There was something very special about being in a place where you can move things around, can use it for your own purposes, can shift things around—we had pop up events, supper clubs, community parties, BBQs, drama classes, the kids played sports, we did everything there. It was a messy space but it was also one that people felt a sense of belonging to. (Gibbin and Bacon 2023: 11)

The collaborative programming at Grow Tottenham exemplifies how flexibly designed spaces can afford a plurality of socially embedded uses.

Figures 3 and 4. Diverse spatial usage at Grow Tottenham, image courtesy of Grow London CIC.

Operator A began to consolidate their operation as a predominantly night-time venue, adding piecemeal renovations and extensions to their portion of the site to support the demands of a growing audience. These refurbishments were self-directed, occurring outside of professional guidance from an architect and included terrace structures, internal linings and subdivisions. As the warehouse meanwhile-occupation progressed beyond the originally anticipated time frames, operations onsite attracted attention from statutory officers within the local council, who approached the leaseholders to formalise Planning and Building Control Applications. Operator B was able to comply more readily with the requirements set out by the local Building Control officer, having developed their space with early engagement from a design professional. Compliance was more involved for Operator A, who subsequently employed the architect to facilitate formal Plan Submissions and a specification of works to retrofit the building to meet specific fire codes within the building regulations.

Ultimately both operators A and B were forced to close their facilities as the surrounding masterplan progressed. Onsite activities and crowds associated with the night-time events organised by Operator B were deemed too disruptive in the context of newly adjacent residential units.

In an emergency meeting with a local authority landlord, 120 minutes have elapsed and it still not clear who is responsible for structural degradation caused by years of water ingress to an external wall at the west of the property. Worse still, the incoming water is significantly polluted, having been incurred as runoff from a poorly levelled car-park which is also owned by the council.

This case study explores the challenges of designing a meanwhile-venue under the jurisdiction of a Local Authority landlord, who is obliged to administer the design process through established bureaucracies of spatial production. This contrasts with the previous case study, which explored more informal meanwhile conditions under a third-party provider.

In 2020, a CBS based in South-East London launched a public investment fund to build a community owned music venue.[6] The operators had secured a derelict building from the council on a peppercorn rent, on the basis that they would refurbish the site to a state of good repair over the course of their 10-year tenancy. The architects conducted a detailed survey of the site in its “as built” state and identified several significant issues which contradicted information which had been supplied by the council to qualify conditions of the lease. Subsequently, the operators were unable to sign the lease in good faith. A lengthy process of renegotiation ensued, as the landlord redefined conditions in the lease. This exchange reveals how forensic aspects of the design process can support the operator’s legal advocation.

However, the CBS was only eligible to receive grants which would help fund extensive refurbishment works once the lease was signed. Other grants were similarly constrained in the context of DIY procurement networks, thereby limiting scope to economise efficiently. These conditions reveal the entangled disadvantages facing grassroots operators when accessing established financial instruments that are unable to accommodate their nuanced needs.

The operator wanted to use the construction process as a platform for collective skill-building in their community. Young people and volunteer groups could contribute to lighter trade elements such as painting, plastering and joinery. While this was an achievable ambition, it exposed the contractors (responsible for all aspects of site safety) to operational risk, requiring additional layers of agreement and coordination between design and construction teams who would need to run overlapping schedules of work. Here, the architects’ knowledge of warranties and liabilities under building contracts provided a solution to this volunteer opportunity without undermining core building works, or the client’s need for compliant (and insurable) building fabrication.

As a community-owned venue, this operator was accountable to the collective aspirations of their community mandate. This required considerable campaign work to garner support from a diverse network of stakeholders including community members, the planning department and the mayor of the borough. The architects implemented a successful co-design process at the design-brief stage, involving periods of discussion, workshopping and evaluation, ensuring the operator’s collective values were consolidated at all stages of the design process. This process of collaborative learning was essential to the organisation’s long-term operational development.

Space is the primary medium through which collective struggles and cultural transformations are experienced and reproduced. DIY venues are a means to resist the co-option of nightlife into regeneration campaigns which sterilise, surveil and privatise our cities. The production of grassroots venues is regulated through regimes of bureaucracy, law and private ownership, which often disenfranchise grassroots practitioners. Assembling these spaces requires thoughtful negotiation and a willingness to take on significant risks. Under these conditions, the grassroots operators described in both case studies present extraordinary determination, resilience and hopefulness in persisting and evolving their DIY programmes.

DIY operations are diverse: encapsulating a range of identities, methodologies and aspirations, which influence the extent to which prospective venues may deviate from conventional modes of building production. Alternative practical methods can include multi-disciplinary occupancies, access to alternative supply chains, adaptative retrofitting and communal ownership.

In London, access to space is contested and politicised. To reclaim spaces for grassroots culture, architects must embed radical sensibilities within their professional practice, ensuring meaningful collaboration with grassroots communities at all design stages to successfully realise programmes of design justice.

Many thanks to Ed Holloway (Director, Beep Studio ltd).

Ella is a multi-disciplinary designer whose practice includes writing, teaching and sound-system, alongside traditional architectural work. As a Part II architectural assistant, Ella works at Beep Studio, supporting grassroots organisations to retrofit brownfield sites for cultural programmes. In addition to her pursuits as a designer, Ella is a sound-system operator with Tanum Soundsystem and member of PATCH Collective, with whom she enjoys organising parties and contributing to printed publications. Ella is an Associate Lecturer at UAL.

ARUP. 2020. Meanwhile Use London. The Greater London Authority. London: GLA.

Gibbin, Izzyand Nicoal Bacon. 2023. Grow Tottenham: Understanding the Impact. London: Social Life. <https://www.social-life.co/media/files/090323_Grow_Tottenham_final_March_2023.pdf>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

Hill, Eleanor. 2019. “Why Haven’t British Architects Unionised?” Failed Architecture, 17 July. <https://failedarchitecture.com/why-havent-british-architects-unionised/>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

Kollwe, Julia. 2023. London Financial District to Have 11 More Towers by 2030. The Guardian, 11 November. <https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/nov/01/london-financial-district-to-receive-11-extra-towers-by-2030>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

O'Connor, Roisin. 2023. “Grassroots Music Venues in Middle of ‘Full-Blown Crisis’, Music Venue Trust Tells Jeremy Hunt”. The Independent, 26 September. <https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/grassroots-music-venues-autumn-budget-jeremy-hunt-b2418593.html>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

RIBA. 2023. “RIBA publishes 2022 gender and ethnicity pay gap data”. RIBA, 27 March. <https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/knowledge-landing-page/2022-gender-and-ethnicity-pay-gap-data>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

Licensing Sub-Committee. (2022). “Minutes of the Open Section of the Licensing Sub-Committee held on Thursday 28 July 2022 at 10.00 am”. London: Southwark Council. <https://moderngov.southwark.gov.uk/documents/g7484/Printed%20minutes%20Thursday%2028-Jul-2022%2010.00%20Licensing%20Sub-Committee.pdf?T=1>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

Time Out. 2019. “Grow Tottenham (CLOSED)”. Time Out, 25 January. <https://www.timeout.com/london/things-to-do/grow-tottenham>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

UCL. 2022. UCL apologises and takes action following investigation into the Bartlett School of Architecture”. UCL: News, 9 June. <https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2022/jun/ucl-apologises-and-takes-action-following-investigation-bartlett-school-architecture>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

[1] Ed Holloway, email to author, 1 December 2023.

[2] Temporary Event Notice (TEN) is a form of single event licence with oversight by the Licensing Authorities for grant.

[3] A quasi-NGO (QUANGO) is semi-public organisation with devolved government power. It formally exists outside of civil service departments but is largely financed and controlled by governmental authorities.

[4] Meanwhile tenancies are subject to the same compliance as permanent arrangements, highlighting the need for better defined discretionary policies for planning and building control permissions in the context of temporary spatial programmes.

[5] See <http://www.growtottenham.org/>, (accessed 17 October 2024).

[6] A Community Benefit Society (CBS) is a type of not-for-profit organisational structure which is registered with the Financial Conduct Authority, and whose revenues and purpose serve the community.