Memory and Nostalgia in Youth Music Cultures: Finding the Vibe in the San Francisco Bay Area Rave Scene, 2002-2004

Independent scholar

In the wake of the major commercial success of rave scenes in the San Francisco Bay Area, accompanied by an increasing crackdown on venues and promoters in the electronic dance music scene, this article follows the “death” of a rave scene and looks at some of the ways young people imagined and engaged with rave culture during that time. Looking specifically at how young people utilized remembrances and nostalgia to imbue their experiences with social meaning, the author provides a tentative case study on youth cultural formation in the late modern era. The article draws upon fieldwork and interviews conducted in the San Francisco Bay Area between 2002-2004.

nostalgia, youth studies, cultural studies, rave scenes, San Francisco Bay Area

Introduction

The Remnants of Rave and Cultural Transformation

The Respondents

Snapshot One: Nostalgia and Change in the Scene

Snapshot Two: Remembering the Rave

Snapshot Three: Consuming Nostalgia and the Marketing of Memory

Conclusion

••••••••

2002. While explaining to friends and acquaintances what exactly I was doing as a post undergraduate - conducting interviews and fieldwork on rave and club cultures in the San Francisco Bay Area - I typically got one of two responses: an excited, "wow… so do you get to go to raves and drop E?" or, a slightly incredulous, "really? I mean… do people still go to raves?" Though these were informal exchanges, they were nonetheless quite telling. The first remark conflated raving and the use of illicit drugs, mirroring media coverage and government scrutiny that culminated in the 2003 passage of the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act, formerly known as the RAVE (Reducing Americans' Vulnerability to Ecstasy) Act (S. 2633, 107th).1

The second comment is more indicative of the varying beliefs around the social and cultural meaning of raves. For those no longer involved, the idea that the rave scene could still exist seemed strangely impossible. A note of disdain sometimes marked these comments, pointing to a tacit indictment of rave scenes as a flash in the pop-cultural pan; what could be understood as the now-passé hedonistic bliss-fests of 1990s neo-hippies and cyber-gurus. Others went on to recall their experiences at raves fondly - relating the extent to which they imagined raves as an exciting and transgressive movement, one whose moment had nonetheless passed.

Yet, a different story emerges from the point of view of those who were still involved. In the Bay Area, large commercial events, or "massives", were held regularly, attracting thousands of attendees. Medium-sized licensed raves that highlighted local talent, organized by small promotion groups and crews, and underground events taking place in quasi-legal spaces, continued to happen every weekend, though with less frequency than years previous (Hunt, Moloney and Evans 2010: 90-4).

The rave scene survived, but in a peculiar way: where on the one hand we had witnessed the proliferation of rave and club cultures across the globe and into various arenas of popular cultural life (Carrington and Wilson 2002), on the other hand, "venues for hearing dance music (not to mention actually dancing to it)" had been subject to increased regulation under the rubric of "the war on drugs and the gentrification of multi-use neighborhoods" (Nicholson 2001; see also Moloney et al. 2009). That is to say, the rave scene, as it existed in the early 2000s, occupied both mainstream and marginalized physical space, where the deregulation of a branded rave culture accompanied a re-regulation of the marginal, the deviant, and the supposed immoral aspects of rave culture (Chatterton and Hollands 2003: 56).

And so it would seem that the metaphorical language of rave as dead was only partly accurate. Yet, as a familiar refrain (reminiscent of the "punk is dead" and "disco sucks" pop-cultural slogans of the past), it had become, and still is, part of a common-sense vernacular that people use to describe youth cultures in relation to late modern society. Using the example of the rave scene, with specific reference to the San Francisco Bay Area, I would like to turn my attention to the question of a "dying" culture based on the narratives and perspectives of those who were involved at the time. The research for this paper draws upon fieldwork and interviews conducted by the author from 2002-2004.2

If, for a moment, we imagine that rave is dead (or more accurately, dead to some and not to others; see Anderson 2009: 20-1), where shall we find its in memoriam? Throughout our interviews, nostalgia and remembrance of times past emerged as a prominent narrative theme. Nostalgic talk tended to present itself without cue, and converged most clearly when respondents were required to negotiate their lived experience and personal attachments with the perceived dissolution of the scene.

The invocation of nostalgia is certainly not unique, nor new to rave cultures. During the early years of rave in San Francisco, one rave-goer issued a missive to his peers that read, "the so-called ravers today show only some sense of community… the house movement is not the latest trend and it's not supposed to be like this" (Raver Rick 1994). Nor are mentions of nostalgia in early 1990s club and rave cultures new (see Fikentscher 76-8; Reynolds 1998: 305; Thornton 1996: 140). Yet, for the most part, nostalgia and how raves are remembered - as a significant part of the vocabulary and imaginary of rave scenes - has received scattered attention as a topic on its own in the literature on rave and club cultures, subcultures, neo-tribes and scenes.

Nostalgia is curious because it links the temporal dimensions of lived experience - encapsulating notions of the past, present and future. In the plainest sense, nostalgia, from the Greek nostos, refers to a longing to return home to a physical place, a past period, or an irrecoverable condition. Some authors in the cultural studies literature, however, have noted that the dislocation, fragmentation and fluidity characteristic of the late modern era have produced a type of nostalgia with no physical or experiential reference point. It is instead predicated on an absence and a longing for a "cultural anchor that is both missing and missed" (Maira 2002, 2005: 203; see also Appadurai 1996). In our interviews, nostalgia for what used to be (idealized raves of yore) pointed to a slippery memory that was based on both the authenticity of lived experience, and upon a collectively imagined, or socially created, past.

What follows then, is a preliminary case study into the imagination, experience and performance of rave, in relation to narratives of memory and nostalgia that appeared in discussions with respondents and other texts relating to the rave scene. I would like to unpack each of these texts to show how borders of cultural formation are drawn and redrawn in the performance of rave. I begin with a summary of the respondents, and turn to a reading of selected "in memoriam" that touch upon the following issues: (1) nostalgia and change in the scene; (2) remembering the social and temporal space of raves; and (3) consuming nostalgia and the marketing of memory.

Between 2002-2004, I conducted seventy-four interviews and analyzed approximately forty additional interviews as part of a larger study on the San Francisco Bay Area electronic dance music scene and club drugs (see Hunt, Moloney and Evans 2010). Interviews were qualitative and in-depth, lasting three to five hours on average, and focused heavily on perceptions and experiences within the rave and club scenes and the social contexts of drug use. Respondents varied in terms of age, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, their drug use and their involvement in the electronic dance music scene, i.e., what types of events they went to, and to what extent they were involved in the scene over time.

Given the size and diversity of the interviews, and the purpose of this article, I have focused primarily on the experiences of thirty-eight respondents who were still involved in the rave scene in the Bay Area, and who tended to go to a similar mix of events from commercial large-scale events, to smaller, semi-permitted parties in warehouses and other converted venues. What follows is a summary of the timing and extent of their involvement, within the context of a long-standing and diverse electronic dance music scene (Moloney et al. 2009; Nowinski 1999, 2000, 2001; Pratt 2000; Reynolds 1998; Silcott 1999; Thompson 2002).

| Question | Range | Median |

|---|---|---|

| How old were they when they attended their first rave? | 13 to 39 | 16.5 |

| In what year did they start attending raves? | 1999-2003 | 1999 |

| How long had they been involved? | < 1 to 9 years | 4 years |

| How old were they at the time of the interview? | 16 to 44 | 20 |

Table 1: Scope of involvement of respondents, 2002-2004 (n=38)

The respondents were on average in their early adulthood - thirteen percent were under eighteen, and fifty-three percent were eighteen-twenty years old. They had also been involved in the scene for several years; only five had been involved for less than two years. But their cultural starting point - when they first started attending events around 1999 - followed nearly a decade after the beginnings of the rave scene in San Francisco, which has been attached to parties thrown by the Wicked collective, Toon Town raves, the Gathering and Come-Unity parties that happened with frequency in the early 1990s. By the mid 1990s, as growing police interventions pressured those throwing parties to find new venues (Silcott 1999: 47-74), the underground scene had begun to transmogrify.

It was not until the tail end of the dot-com boom of the late 1990s - during the massive take off and upsurge in popularity of commercial raves, and a growing struggle over regulation in the nighttime economy (Hunt, Moloney and Evans 87-9; Pratt 2000a) - that most of these respondents attended their first events. Most reported going to their first rave in Oakland, about thirty minutes outside of the city, in warehouses and abandoned storefronts; and a smaller number attended raves for the first time at licensed events held in stadiums and arenas like the Cow Palace, 3Com Park, and Bill Graham Auditorium in and near the city.

At the time of the interviews, these respondents were involved in overlapping scenes - they found out about events through specific websites and record stores (notably Skills and Frequency 8), and chose events based on a similar set of DJs they followed, and promotion crews they liked (Skills, Unity, Happy Kids, Feel Good, Elektrosorcery and Audio Metamorphosis, came up numerous times, for example). Despite these similarities, they had diverse views on the scene, where they stood in it, its personal significance and their reasons for attending. Only about a quarter went to clubs regularly, and younger respondents cited their age as a barrier. Compared to raves, clubs were not as personally significant to them, and they would usually attend to see a particular DJ perform.3

Nostalgic narratives emerged throughout our interviews, and they often did so in a peculiarly collapsed and often self-contradictory manner. That is, a respondent would often wax nostalgic when describing the present in relation to the past (on any topic from music, drug use, types of behavior and dress, to perceived changes in the scene) - yet, this authentic past was often in direct contradiction with their own lived experience; self-admittedly in reference to a past they had not taken part in (spanning on average four-six years); or in reference to an arbitrarily demarcated generational past (sometimes in reference to the 1970s counter-cultural generation, other times in reference to the ever-appalling "little kid", more specifically, the "thirteen-year-old on drugs").

The following quote from Jamie, who had been involved in the rave and club scene since 1999, touches on a number of these points:

What's so good about the rave scene is that it's just so open to anyone… but it is a really sad thing when you see thirteen-year-olds, fourteen-year-olds who are there. And they're just doing drugs first of all. And who knows, they might have a really deep appreciation for the music, but… if you're gonna be here you should know who's spinning. You should be educated about the rave scene… You shouldn't be here because you know this is trendy and this is the new thing to do… Last year or the year before… it got really exploited. It was on the news - 20/20… [It was] so frustrating for me because when I tell… my family or anyone that I'm going to a party and they see that it's just associated with drugs, cuz that's what they see on television, it's like I have to prove myself… So many people go there for the music and for the culture… You gain so many friends… and just… feel like part of something… I don't really condemn anyone… But… if you're gonna do drugs, you know, I don't know… do drugs responsibly… It was such an underground thing. I mean, I didn't party when it was really underground. And how people say the parties were back in those days… It wasn't exploited, and parties weren't getting broken up. And people were responsible. And people were there for the 'right' reason… Sometimes it's like these E-tards are just here doing drugs… setting such a bad example. But other times, I'm like - you know what - people are just gonna do what they're gonna do. They wanna experiment. They wanna have fun.4

The prevalence of self-contradiction in this case has to do with the internalized belief that the rave scene should exist as a cohesive whole ("what's so good about the rave scene is that it's just so open to anyone" or, the oft-cited rave ethos of "PLUR", which stands for "peace, love, unity, and respect" and invokes a sort of unity-in-diversity logic), and the fact that the rave event depends on diverse individuals coming together to experience a collective energy. This sentiment becomes increasingly contradictory given the ever-changing nature of the rave scene.

Jamie does not want to condemn the thirteen-year-olds or "E-tards" for ruining raves (blame is deflected to popular media, other faceless abstractions, ignorance, or exploitation), because being judgmental toward other rave participants is contrary to the rave experience as it has been learned, imagined, experienced and internalized. An emotional dilemma arises when those outside of the scene are unable to view the positive aspects of her experience, including a deep appreciation for the music at raves and a strong sense of belonging and inclusiveness. She is put into a defensive position and feels frustrated, indignant and misunderstood by family and peers.

Other respondents were far less forgiving, and placed the blame of a ruined vibe squarely on the influx of "others": people who used drugs irresponsibly, acted violently or in an overtly sexual manner, to name a few. Throughout our interviews, discussions about the irresponsible drug user tended to illicit the most ire and the most self-contradiction. In the most extreme cases, these accounts included a revised personal history that neglected the crucial role drug use played in their own early experiences of the scene. For the most part, however, respondents criticized the way drugs were used, not drug use in itself. This was something that had to be learned, as Ryan's description of his first time using MDMA ("ecstasy" or "E") at a rave demonstrates:

I was like, 'You know, I don't feel anything'. And my friends looked at me and they were like, 'Your eyes are huge'. And I was like, 'Really?' And it was like, 'Yeah, your eyes are huge'. And then all of a sudden… he's like, 'Well… come dance with me'. And I was like, 'Uh, all right. But you know, I feel like sitting down'. And I guess I sat down in the middle of the dance floor, cuz I didn't know how to feel, and he started kicking me, and he's like, 'You are my best friend. You are not doing this to me. Get up'. And I was like, 'Why are you kicking me?' You know. And he's like, 'Get up… You will not be an E-tard'. And, you know, that's what we call people who are on E who just like, they sit on the floor, and they give massages to each other and, you know, cuz we think they're retards, you know, we call them E-tards.5

Certainly, idealized rave attendees do not arrive in a spontaneous vacuum. Appropriate drug using behavior is learned from friends, or from the lived experience of raving. Nostalgic narratives around a time when "people were responsible" and "were there for the right reason" inform the social practices and cultural norms of raving. In the above example, the physical instantiation of "no-no" behavior (privileging drug use above dancing, music and social cohesion, by sitting on the floor), is quite literally embodied, and dispersed across the subjective experience of the event itself.6 The annoyance with drug using "others" (not to mention all the other "others") comes from a perception that they are unable or unwilling to learn particular codes of behavior.

Siokou and Moore (2008), in an article on the commercialized rave scene in Melbourne, argue that the prevalence of nostalgia for raves of the past can "be read as claims to subcultural capital, to the possession of an 'authentic' rave identity" (51; drawing on Thornton 1996). While nostalgia may be used as a claim to "cool" in some cases, I found that for most respondents, nostalgia was simply an interpretive tool to give coherence to an increasingly incoherent cultural experience. Nostalgia, in such a case, manifests itself around dissatisfaction in the present, and on the assumption of "an earlier time of cultural wholeness that is now at risk of fragmentation" (Maira 2005: 203; see also Chase and Shaw 1989).

In particular, harking to imagined raves of the past gave meaning to the itinerant space they occupied, between underground-commercial, authentic-fake, unified-fragmented (Anderson 2009; also Maira 2002). The prevalence of nostalgia around drug use, in particular, reflects a profound emotional and localized response to the perceived vilification (the RAVE Act loomed on the horizon) of a scene they identified strongly with. It also points to a profound disappointment that their lived experiences - overwhelmingly pointing to the fact that drugs can be used responsibly, and that the pleasures of the rave scene extend beyond drug use itself - were not taken seriously.7 Every single respondent I spoke with felt that the media unfairly portrayed raves, clubs and drug use.

Finally, there are times when nostalgia is associated less with perceived changes in the scene and more with changes in the person who perceives them. As examined in the next section, the pursuit of an "authentic experience" is associated with capturing a particular temporality, not just within an event or scene, but also in one's life. Paul, who was involved in earlier iterations of the scene, says:

I mean the scene is different certainly now than it was then. I don't know if it's any worse. It probably is in some ways. It's probably worse for me in some ways, because, you know, I can't do some of the things that I used to be able to do… 'Kids these days will dance to anything'. You know, like [that's] my problem and not theirs… One starts to sound like… some fifty-year-old Deadhead, who still listens to his, you know, fucking Grateful Dead tapes over and over again and mourns Jerry's death. You know. Or something. The techno version of that.8

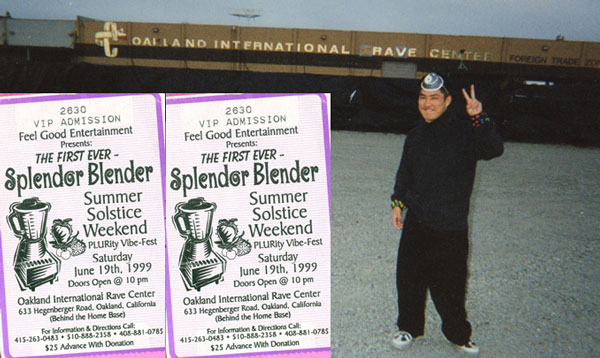

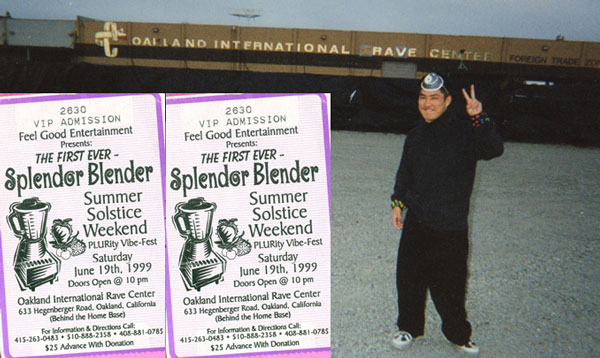

Beneath the imbrications of thirteen-year-olds on drugs, clueless trend seekers and other signifiers of a ruined experience resonates an earnest, and difficult to ignore, sense of longing and loss for a lived experience. The following is an excerpt from a message board discussion upon the news that Home Base (a favorite East Bay warehouse venue that housed massive raves from the mid 1990s until it was shut down by the City of Oakland at the end of 1999; see Pratt 2000; see image below), had burned down in October 2005. FUTUREISNOW141 commented in a thread called "Remembering Home Base", and the post reads like a eulogy, a memoriam of a youth past:

IT HURTS BUT THE MEMORIES LIVE ON

I DISCOVERD MARS AND MYSTRE THERE, SOMETHING THAT TO THIS DAY HAS CHANGED MY LIFE. I REMEMBER THE FIRST TIME I HERD SAVE THE RAVE. I REMEMBER THE VIBE BEING THE BEST THING THAT COULD BE. THE HUGE OUT SIDE AREA WAS AWSOME. I REMEMBER THE INTERNATIONAL TRADE CENTER SIGN BEING TURNED INTO THE INTERNATIONAL RAVE CENTER. I REMEMBER TALKING TO PEOPLE FROM ALL OVER THE UNITED STATES COMING TO WHAT WAS KNOWN AS THE BEST PLACE TO ATTEND FOR A RAVE IN THE UNITED STATES.

I REMEMBER THE FIRST TIME I WALKED INTO THE BUILDING, I GUESS WHAT I AM TRYING TO SAY IS, THAT WAS A PLACE WHERE I SHARED SOME OF MY FONDEST MEMORIES, I WAS BORN INTO THIS CULTURE AT THE BUILDING. I HAVE MISSED IT FOR THE 5 YEARS IT HAS BEEN GONE. THE LAST EVENT I ATTENDED THERE WAS SPIRIT OF GIVING 1999. MY HEART WAS BROKEN THAT NIGHT AND SOME THINGS HAVE NEVER BEEN THE SAME. SKILLS DOES A GOOD JOB OF BRINGING BACK THE OLD SCHOOL VIBE BUT THEY CAN NEVER BRING BACK HOME BASE.9

Figure 1: At Home Base in 1999. The Oakland International Rave (Trade) Center.

Used with permission from Le Sheng Liu, http://www.leshengliu.com

In this text, memories of times past are folded into physical space and a sense of generational ownership. There is something about the temporality of youth as a psychosocial and historical construct that lends a specific valence to such sorrowful talk. To juxtapose two adages: one can be "young at heart", but "you can never be young again". And similarly, while lamenting the end of his or her time at Home Base in 1999, FUTUREISNOW141 notes that "Skills does a good job of bringing back the old school vibe but they can never bring back Home Base". He or she is not literally asking for Home Base back - as if the physical building would somehow offer solace for a broken heart (perhaps it would, this is discussed in the third snapshot later in the article) - but more importantly, the subjective temporality that Home Base represented.

The idea of being "born into", or as some of our respondents said, "growing up" with others in the rave scene, was a significant aspect of the rave as an experience: an encapsulation of youth, maturation and coming into the world. And though this usually coincided with biological age - most of our respondents were exiting adolescence and entering their twenties - it also had much to do with a maturation process within the scene itself. Josh, who went to his first rave at age thirty-nine, says he was very naïve when he first started attending, and recalled getting scolded by a sixteen-year-old for not knowing enough about the drugs he was taking. The common experience, regardless of biological age, according to him, was having a space to experience youthfulness:

You have someone who's maybe like an eighteen-year-old guy with like colorful, fuzzy things like hanging off of his clothes… with a Sesame Street backpack, you know, they're not acting their age either, so they're seeing it like, 'Oh, I'm eighteen, I'm a successful college student, I have a future, but there's still that part of me that I treasure from when I was eleven years old'. And they're just closer to it than I am, but, I don't think I'm reaching back to eleven myself, I'm reaching back more to like seventeen (laughs).10

On the opposite side of that continuum, many cited their age as the reason their interest in attending events was declining, saying they had started to "feel too old", or that they had "grown up" and needed to deal with the responsibilities of school work, making money and adult life.

Besides the experience of youthfulness and growing up, the other "remembering" of the scene was related to the social and temporal space of the rave event itself. Our respondents described raves as a place to have fun, "a happy place on earth", a place to belong, "my second home", a place to feel safe and free, a place to escape and let go, "my utopia", a place that gives "faith in humanity". Almost uniformly, however, when recalling what was/is good about raves, our respondents talked about raves as a place to "feel the vibe" - as FUTUREISNOW141 commented, "I remember the vibe being the best thing that could be".

When asked to define what the "vibe" entailed, I often received very truncated answers, no matter how talkative a respondent had been earlier in the interview. According to our respondents, a good vibe amounted to good music, friendly people and everyone dancing together. Much of the rich literature around rave and club cultures has devoted itself to capturing the tangible emotional atmosphere of events in words, examining the peculiar combination of music, crowds, dancing and sometimes drug use that amounts to much more than the sum of its parts (Fikentscher 2000; Gilbert and Pearson 1999; Malbon 1999; Reynolds 1998; St John 2004).

Describing what he meant by "feeling ecstatic" at raves, Daniel, who attends raves sober, said:

I find I have those… ecstatic moments when I am listening and dancing to music that I am really getting into, and more importantly… it has to be really energetic and… like if I look back [into the crowd] and just see everyone dancing away and full of energy and… not really caring about much else other than dancing, that's when I feel, I guess, the most ecstatic, like those are the best parts of partying for me, is really feeling the music and seeing that other people are too. And not just other people, but like the whole room, for example.11

This description points to the ways in which such an atmosphere is imagined, felt and perceived on a personal basis, but also experienced within a creative and social site of reception, through the collective participation and energy of the crowd. Jamie, describing the joy of dancing at raves, put it this way:

That's what's cool too about the rave scene is that you can go there and you can dance however you want and however you feel the music. And it's not like a club where you're being looked at and scrutinized… But it's hard to describe it. People really let loose. And you're in your own world. You're zoned into yourself and your body and your mind. And you're just like listening and taking in the music. And whatever comes out your body just reacts to that.12

For Jamie, dancing to music at raves is the body's physical interaction with music in a particular environment, where you're not "being looked at and scrutinized", allowing her to be "zoned into… [her] body and mind". Though Daniel and Jamie frame their ecstatic experiences in slightly different ways, they both talk about capturing an existence in the moment itself - "feeling the music" - within the dancing crowd. This phenomenon is related to the interactivity and simultaneity involved in creating a vibe, a "collective energy that can be experienced on an individual basis" (Fikentscher 2000: 81; see also Malbon 1999) and a distinct sensation of "being alone together" (St John 2004: 31, quoting Moore 1995).

Figure 2: Dancing at "Eridanus", a party thrown by the Preserve crew, 22 February 2003

Used with permission from Deciblast, http://www.deciblast.org

Figure 3: Giving and receiving a light show with photon lights, date unknown

Used with permission from Deciblast, http://www.deciblast.org

Not to ignore the experience of drug use as another component in the textural space of rave, the psychological effects of ecstasy that most respondents cited were feelings of openness toward other people, and closeness with others around them. Characterized as a life affirming experience, ecstasy use made some feel "like a little kid" by recreating a sense of amazement, while it made others feel more open-minded or at ease with themselves and others. Malbon (1999) describes ecstasy use as a means to initiate, prolong, or intensify the effusive and emotional environment at clubs and raves. Brett, who attended raves for about two years before trying ecstasy at a rave, describes his first experience using:

[Simon Apex] plays like happy hardcore or something. It's like headache music when you're like sober. But… they announced that he was playing a set next, and so he started off the set, and it was very bright and happy and bouncy, and I was like, oh, shit. So I stumbled my way up to the front and I was just jumping up and down, hooting and hollering, and I grabbed somebody's whistle and started blowing it. I don't know. I got very… very captured in the moment. We stayed there well until the end. I started to feel like I was coming down. It was sorta depressing, knowing that everybody was starting to leave the party. It was sorta like, that mysticism, that magic is gone now. You know, the lights were on, the music stopped. You can see people cleaning up, people saying bye, giving hugs and stuff. But, you know, I sat there and I was like, 'I don't wanna move. I don't wanna go anywhere. I feel safe, comfortable, and happy here. This is where I wanna be'.13

Brett not only experiences a collapsed sense of time (note the lapse between "I don't know. I got very… very captured in the moment" and "we stayed there well until the end"), and a strong sense of belonging ("I feel safe, comfortable, and happy here"), but also an immediate reflection upon and longing for the experience he just had ("I don't wanna move…"). Reveling in the "afterglow" of the moment (Malbon 1999), and the desire to "go back" figured into a good number of interviews describing positive rave experiences.

In all of the cases above, capturing a particularly ecstatic and ephemeral moment was what made raving poignant for our respondents. The pleasure of those moments can "endure well after their temporal and far beyond their spatial epicenters" (Malbon 1999), living on in memories of times past. Nostalgia for raves past - as in the opening passage of this section - manifests in the demand for a shared present (St John 2004; see also Fikentscher 2000). It is nostalgia for a particular time (within a developmental frame of experiencing youthfulness or being born into a culture), and for the temporal and experiential moment of rave itself.

While nostalgia is sometimes dismissed as a lazy reaction to a changing world, it can also help orient one's gaze upon the future. As Chase and Shaw (1989) point out, the imagination of an ideal past can only happen after an ideal future has been conceptualized (9). When asked what could be done to improve the rave scene, respondents usually offered one of two responses: go "underground", outside the purview of nightlife regulation, to help revive the scene. Or, bring the positive experience of raving into the world of permitted clubs and venues to help preserve the scene. Either solution, they said, would need to "bring back the vibe".

Below, I will look at two promoters who decided to do just this - what Tammy Anderson (2009) terms cultural "restoration" or "preservation" in her adept analysis on the decline of rave culture in Philadelphia. In doing so, these Bay Area promoters attempted to invoke the past in the present through collective reenactment. The Berkeley promotion company, Skills, did this quite literally in June 2004 when they organized a party dubbed "1998". Tickets sold out so quickly that they decided to hold a second party that weekend called "1999". The flier declared that "all DJ's [would] be spinning sets from the 1999 era ('98-'00)". Mars and Mystre, two DJs credited for a specific brand of San Francisco trance, would be reunited on the decks, three years after they had split ways.

The following summer, San Francisco ravers were invited to travel back in time once more. The destination was 2000 - the "year of the rave". The following is an excerpt from the "Imagine 2000" party flier (see image below):

IMAGINE 2000

is being thrown in tribute to one of the Bay Area's most historic dance years 2000!!! In the year 2000, the Bay Area dance scene was faced with a difficult challenge, Anti-Dance Legislation had recently been passed and many of the Bay Area's landmark venues had been closed; namely Home Base and 2nd & Jackson. Despite an onslaught of public pressure the Bay Area Dance Scene did not collapse. Instead it responded with a message of Peace, Love, Unity and Respect. It was during this time of hope and determination that SKILLS and UNITY created two of San Francisco's most positive and successful events: Popsicle & Imagine.

BRINGING BACK UNITY:

To help bring back the vibe & energy of 2000, SKILLS has enlisted the help of the legendary crew, UNITY. Best known for throwing the only (Rave/Party/Late Night Dance Event) to be held inside San Francisco City Hall, UNITY had an unequalled reputation for creating an environment of Positivity, Creativity and Community. Together, SKILLS and UNITY plan on making Imagine 2000 the most magical event in Bay Area history!!!

Figure 4: Flier for "Imagine 2000: The year of the rave" party, thrown by Skills and Unity on July 30 2005

Used with permission from Le Sheng Liu, www.leshengliu.com

If it is not already obvious, the sense of time denoted in these fliers is uncanny, and marks the life span of a raver at far less than five years. The "era" spans only three years. This curious aspect of the event was not noted by respondents planning to attend the party. For many, 1998, 1999 and 2000 operated as significant marking points, either denoting the beginning of their involvement in the rave scene, or years they had mythologized. These years, as the flier points out, were also marked by increasing anti-dance legislation that drastically changed the Bay Area dance scene (see Moloney et al. 2009).

In some ways, Skills, a small commercial enterprise founded by two Bay Area DJs, with its roots in the mid-1990s Bay Area rave scene, went "back to the future" of 1998, 1999 and 2000 in an attempt to capture something about that particular past in the present. Many of the respondents I interviewed cited Skills parties among their favorites because they captured the "mood" and "old school vibe" of parties past. The Unity crew, who organized parties to raise funds for local charitable organizations, was almost universally loved by our respondents, and had not thrown an event in a couple of years.

From the advertisement, it is also clear that an ersatz version of the past was being marketed: attendees were encouraged to arrive early, in order to receive "vintage gear" from four-six years prior. They were encouraged to "feel the vibe" by wearing their "craziest, funkiest & sexiest party outfits" - getting the chance to "dance on stage with the Sexy Skills Sirens and Beautiful Unity Glow Girls". The idea of sexy sirens on a stage might seem quite appalling to those who were involved in the scene around 1999 or 2000, and was probably more akin to the club than the rave scene at the time. This particular reworking of the past, in order to make a successful event in the present, is not entirely surprising.14

It is also no surprise that Skills parties were usually advertised as "100% permitted events" with a "zero-tolerance drug policy", ostensibly erasing two aspects of the rave that had so characterized its beginnings. The mid-2000s saw the continued regulation of venues and an increasing influence of the private sector over nightlife (Hunt, Moloney and Evans 2010: 90). Promoters seeking a "legitimate" stake in the nightlife economy were likewise required to adopt its rules and regulations.

This is not to say that "legitimate" raves were the only raves in the Bay Area at the time. As I noted earlier, electronic music dance events continued in a variety of places. Rey, who worked with Preserve (whose slogan was "Preserve the vibe"), a newly formed promotion crew, described throwing an illegal "renegade" party at Home Base in November 2004. The warehouse was initially supposed to serve as a "map point" (a place where attendees would go to receive directions to the actual rave). But after dismissing the risks of throwing a party in an illegal space - losing equipment, jail time and a substantial fine - the crew decided to throw the party there in order to revive the "good memories", and to do "something everyone wanted".

We actually weren't planning to throw the party there. That was actually supposed to be the map point for another location. And we kinda checked it out three days before, and we found out the front gate was open, and we thought it would be fun to just walk around. Then we found out the door was open, so we went in and spent a couple hours there, and we figured that like nobody was coming around and so, you know, that night we just decided we're gonna throw it here and just surprise everybody. And it was kind of a mess throwing it, just because like you know, the whole fear factor like… if cops come at any time, we're just completely screwed, and we're all going to jail pretty much (laughs)… There was this hole in the gate that people had to go through to get in, and it was just… it was definitely an experience, but at the same time… you had people that went to the party that were crying the second they walked in, they were just like so amazed that they could actually go there again… We were only charging like $5 and people were… trying to give us money at the end of the party saying like, you know, this was definitely worth it and we wanna give you more, cuz you guys deserve it. I mean, we didn't really lose money on the party, but you know, like all the DJs that we had were you know, Preserve DJs or Audio Metamorphosis DJs, so didn't really have a budget for anything. But there was just that fact that you know, we just tried to do something to you know, have something that everybody wanted.15

Would the brokenhearted gain solace by returning to Home Base? It seems that some would. Their feeling of amazement, as Rey described it, derived from the reclamation of space that represented a particular time in their lives, and a particular moment in the Bay Area rave scene. Rey's sense of gratification, it seemed, drew from his crew's reenactment of the past. Breaking into a space, squeezing through holes in chain-link fences, being on watch for police, and a disregard for getting caught, were all part of the imagined past of "renegade" raves.

It is clear that, from 2002-2004, people still attended raves and rave-like events, but in an increasingly regulated environment that saw the decline of the lived-experience of raving. Nostalgia had become a predominant way of experiencing and giving meaning to an imagined and remembered past that was both missed and missing (Maira 2005). In the case of the Bay Area rave scene in the early 2000s, nostalgia operated at a few different levels, and pointed to a slippery memory based on collectively imagined, as well as lived, pasts.

First, it functioned as a powerful trope for young people to make emotional sense of a culture under perceived threat of dissolution. Nostalgia also became embedded in the cultural vocabulary that young people used to perceive their experiences of rave culture and how it had changed over time, regardless of "historical accuracy". Second, it reflected a legitimate longing for a particular concatenation of youthfulness, and an overriding desire to recapture the emotional aura and vibe of raves. For these young people, who began attending raves in 1999, memories of youthfulness and the vibe were connected to a particular moment in the history of the Bay Area rave scene - what could be categorized as its second wave of widespread popularity. Third, nostalgic renderings of the past were used to both market and mobilize the rave scene into the future.16

In the vignettes above, the young people involved in the Bay Area rave scene took on a variety of nostalgic subjectivities that strongly informed the remembrance and re-imagining of a particular space and time that had fallen out of reach, had become increasingly difficult to find, or had ceased to exist. The intensity and prevalence of nostalgia in this late-modern youth culture, however, indicates a continued desire to seek out such spaces, irrespective of regulatory structures within the nighttime economy (see Measham 2004). In re-imagining the past, these young people drew and redrew the lines of a "dying" culture, and positioned themselves toward the future.17

••••••••

I would like to thank Dr Geoffrey Hunt for the opportunity to work on this project and for supporting me in my endeavours. Thank you to Graham St John and two anonymous reviewers who offered their insight. And my utmost gratitude goes to the diverse and always fascinating group of people who shared their imaginations and experiences with us.

Anderson, Tammy L. 2009. Rave Culture: The Alteration and Decline of a Philadelphia Music Scene. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Carrington, Ben and Brian Wilson. 2002. "Global Clubcultures: Cultural Flows and Late Modern Dance Music Culture". In Mark Cieslik and Gary Pollock (eds), Young People in Risk Society: The Restructuring of Youth Identities and Transitions in Late Modernity, pp. 74-99. Burlington: Ashgate.

Chase, Malcom and Christopher Shaw. 1989. "The Dimensions of Nostalgia". In Christopher Shaw and Malcom Chase (eds), The Imagined Past: History and Nostalgia, pp. 1-17. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Chatterton, Paul and Robert Hollands. 2003. Making Urban Nightscapes: Youth Cultures, Pleasure Spaces and Corporate Power. London: Routledge.

Fikentscher, Kai. 2000. "You Better Work!": Underground Dance Music in New York City. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Gilbert, Jeremy and Ewan Pearson. 1999. Discographies: Dance Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound. London: Routledge.

Hunt, Geoffrey, Molly Moloney and Kristin Evans. 2010. Youth, Drugs, and Nightlife. New York: Routledge.

Huq, Rupa. 2006. Beyond Subculture: Pop, Youth and Identity in a Postcolonial World. New York: Routledge.

Maira, Sunaina. 2002. Desis in the House: Indian American Youth Culture in New York City. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

---. 2005. "Cool Nostalgia: Indian American Youth Culture and the Politics of Authenticity". In Helena Helve and Gunilla Holm (eds), Contemporary Youth Research: Local Expressions and Global Connections, pp. 197-208. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Malbon, Ben. 1999. Clubbing: Dancing, Ecstasy and Vitality. New York: Routledge

Measham, Fiona. 2004. "The Decline of Ecstasy, the Rise of 'Binge' Drinking and the Persistence of Pleasure". Probation Journal 51(4): 309-26.

McRobbie, Angela. 1994. Postmodernism and Popular Culture. London: Routledge.

Moloney, Molly, Geoffrey Hunt, Natasha Bailey and Galit Erez. 2009. "New Forms of Regulating the Nighttime Economy: The Case of San Francisco". In Phil Hadfield (ed), Nightlife and Crime: Social Order and Governance in an International Perspective, pp. 219-36. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nicholson, Peter. 2001. "Coming Out: Is the Mainstream Ready for House Music?" SF Bay Guardian, 14 February. http://www.sfbg.com/AandE/35/20/coming.html (accessed December 2005).

Nowinski, Amanda. 1999. "Coming Through". SF Bay Guardian, 24 November. http://www.sfbg.com/AandE/Electric/eh3408.html (accessed December 2005).

---. 2000. "House Nation Rises". SF Bay Guardian, 15 March. http://www.sfbg.com/AandE/Electric/3424.html (accessed December 2005).

---. 2001. "Save the Rave?" SF Bay Guardian, 28 February. http://www.sfbg.com/AandE/Electric/3522.html (accessed December 2005).

Pratt, Rob. 2000. "Raves Get Local". MetroActive, 5 April. http://www.metroactive.com/papers/cruz/04.05.00/undergroundbeats-0014.html (accessed December 2005).

Raver Rick. 1994. "WAKE UP!" XLR8R 9. http://media.hyperreal.org/zines/xlr8r/guest.editorial (accessed December 2005).

Redhead, Steve. 1990. The End of the Century Party: Youth and Pop Toward 2000. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Reynolds, Simon. 1998. Generation Ecstasy. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

Silcott, Mireille. 1999. Rave America: New School Dancescapes. Quebec: ECW Press.

Siokou, Christine and David Moore. 2008. "'This is Not a Rave!' Changes in the Commercialised Melbourne Rave/Dance Party Scene". Youth Studies Australia 27(3): 50-7.

Stahl, Geoff. 2003. "Tastefully Renovating Subcultural Theory: Making Space for a New Model". In David Muggleton and Rupert Weinzierl (eds), The Post-Subcultures Reader, pp. 27-40. Oxford: Berg.

St John, Graham. 2004. "The Difference Engine: Liberation and the Rave Imaginary". In Graham St John (ed), Rave Culture and Religion, pp. 19-45. London: Routledge.

Thompson, A.C. 2002. "Life During Wartime - Operation: Get the Ravers". San Francisco Bay Guardian, 24 July. http://www.sfbg.com/36/43/x_new_war.html (accessed December 2005).

Thornton, Sarah. 1996. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Cambridge: Polity.

Wilson, Brian. 2006. Fight, Flight or Chill: Subcultures, Youth, and Rave in the Twenty-first Century. Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen's University Press./p>

Eileen M. Wu received her BA in Political Economy from the University of California, Berkeley, and her MA in Sociology from the New School for Social Research in New York. She is a former fieldworker for the Institute for Scientific Analysis, San Francisco. For the past several years, she has worked as a consultant in international development, with a focus on youth and the global AIDS epidemic.

1. Signed into law by George W. Bush on 30 April 2003 as a tag-along on the Amber Alert Bill, and initiated by then Senator Joe Biden (Delaware, Democrat), the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act extended the scope of federal anti-crack house laws of the 1980s to club and rave promoters, making it easier to prosecute them for failing to prevent illicit substance use at their events - subsequently criminalizing a "contemporary and highly popular youthful activity" (Hunt, Moloney and Evans 2010: 84).

2. Collection of data for this article was made possible by funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA14317), Principal Investigator Dr. Geoffrey Hunt. For a comprehensive summary of the respondents and methodology of the study, see Hunt, Moloney and Evans (2010: 27-50). Additional information on the pulse of the electronic dance music scene was gathered through print fliers and electronic sources such as Bayraves.com, Ravelinks.com, SFRaves.org, the FnF mailing list and the DJ Denise mailing list.

3. Though issues of gender and ethnicity are not discussed in this article, I would like to give the following demographic information: the respondents were 58% female, 42% male. Ethnic breakdown was reflective of the diversity in our overall sample: 42% White; 32% Asian/Pacific Islander; 11% African American; with the remainder of the respondents identifying as Native American, Latina and primarily of mixed ethnicity.

4. Jamie, age 23, interview with author (Institute for Scientific Analysis [ISA], San Francisco), 12 April 2003. Pseudonyms have been used for all respondents.

5. Ryan, age 19, interview with author (ISA, Alameda), 22 July 2003.

6. Malbon (1999) notes that the ecstatic experience is littered with these moments of self-conscious obligation to monitor ones behavior, removing the dancer from their momentary reverie (111). See also Thornton (1996) who might understand this as an enculturation of authenticities and "authentic" behaviors.

7. A minority (two) of the respondents I focused on for this article reported prolonged problematic use with ecstasy.

8. Paul, age 33, interview with author (ISA, San Francisco), 23 January 2004.

9. FUTUREISNOW141, posting on Skills Message Board on 16 October 2005: http://p073.ezboard.com/fskills69311frm2.showMessage?topicID=1779.topic (accessed 1 December 2005). A few explanatory notes on the names and places mentioned in the post: Mars and Mystre are DJs, and "Save the Rave" is one of their rave anthems. The crews throwing parties at Home Base would convert the sign at the front of the building to read "International Rave Center", and Skills is a local promotion crew started by two local DJs.

10. Josh, age 44, interview with author (ISA, Alameda), 21 March 2004.

11. Daniel, age 21, interview with author (ISA, San Francisco), 1 August 2003.

12. Jamie, age 23, interview with author (ISA, San Francisco), 12 April 2003.

13. Brett, age 20, interview with author (ISA, Alameda), 18 September 2003.

14. The role of consumption and nostalgia in dance music scenes has been contested - some have argued that nostalgic styles, images and music are marketed to further exploit and commercialize raves (Wilson 2006). Others in the literature have noted how the consumption and recycling of past styles, as well as pastiche and parody in music cultures, have played an integral role in the making of new music cultures (Huq 2006: 108; Redhead 1990: 94; see also McRobbie 1994: 174).

15. Rey, age 21, interview with author (ISA, Alameda), 17 March 2004.

16. As a postscript, many of the small-scale promoters that were discussed in this article no longer appear to be throwing parties, pointing to the many difficulties involved in preserving and restoring cultural elements of past raves (Anderson 2009: 133-4). Skills is one of the only commercial (rave) promoters founded in the mid- to late 1990s that is still throwing parties. They continue to throw "Imagine 2000" parties with profits going to local charities.

17. I am drawing upon Stahl's (2003) discussion of space, imagination and agency (31-35); see also Appadurai (1996).