Towards a Granular Study of Scenes at Vancouver’s New Forms Festival

Université de Montréal (Canada)

DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2014.06.02.11

Over the past fourteen years, Vancouver has slowly come of age, shifting from a relatively inexpensive and obscure, industrialised settler port on the West Coast of Canada—home to cult sci-fi from Stargate SG:1 to The X-Files, writers Douglas Coupland and William Gibson, industrial pioneers Skinny Puppy and an early and influential acid house scene—to its newfound identity as an overdeveloped and increasingly unaffordable bling city. But Vancouver’s economic transformation into a seafront sequester for the wealthy has also had its cultural upswing, of sorts. For years Vancouver was parroted as “No Fun City” thanks to overzealous and culturally conservative bylaws blocking entertainment and the arts. For the most part, and even with the loosening of Provincial liquor laws, little has changed. Various arts venues continue to be squashed by the interests of developers building uninhabited investment condos. Yet this broader conflict over affordable housing in general has nonetheless catalysed action in the arts community, sprouting something of an internationally-recognised EDMC festival scene, in no small part thanks to the hardy efforts of the New Forms Festival.

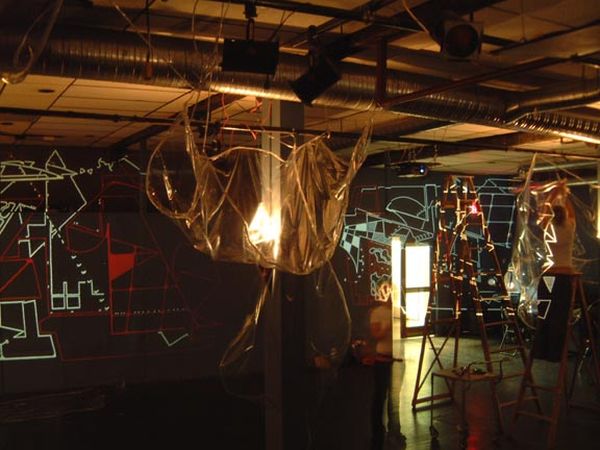

Figure 1. Setting-up Glitch & Granular at the 2002 New Forms Festival. Olo J. Milkman’s projected line-art is visible behind Triina Linde’s ceiling-hung installations. Photo credit: Olo J. Milkman.

New Forms initially launched in 2001 as a small street festival focusing on hip-hop, post-rock, and other “new forms” of music—surprisingly for festival-goers today, it featured nearly everything save for electronic music. This was to change, however, as with the 2002 edition—and under my curatorial efforts—NFF launched its first electronic music showcase entitled “Glitch & Granular”. Taking place at the Video-In (VIVO) media arts centre on Main Street, the showcase featured Mitchell Akiyama, Joshua Kit Clayton with Sue Costabile, local artists Ben Nevile and ssiess, video artists Camille Baker and Owen J. Milburn, and myself. The space was transformed with light-refracting installation art from Triina Linde and line-art projections by olo j. milkman (visual gallery here).

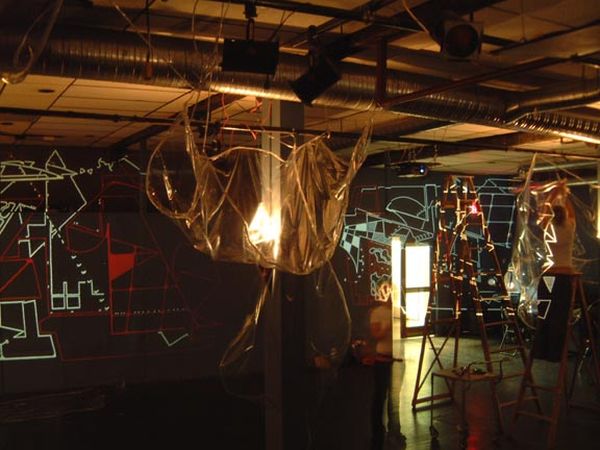

Figure 2. Left to right: Camille Baker, Owen J. Milburn, tobias c. van Veen, ssiess. Owen and Camille ran interactive visual Max/NATO patches using tobias and ssiess’ audio as parameter input. Photo credit: olo j. milkman (2002).

It is worth revisiting the scene of NFF’s first electronic showcase in lieu of the “Timeline” as presented on the festival’s website. Although festival co-founder Malcolm Levy suggests that it was his 2003 visit to Transmediale in Berlin that introduced him to the multi-purpose format of a media arts festival [1], it is worth pointing out that Vancouver had already explored transgressive and immersive media arts during its preceding decade of events that intersected rave culture. I raise this point precisely because these interstitial events subsisted liminally on the boundaries of both rave culture and the (increasingly) institutionalised festivals that followed. Neither a rave nor an arts-council-funded festival, neither a shindig nor a showcase, a spectacle show nor a gallery exhibition, such events and their organising collectives often fall into historical neglect, omitted from a scene’s historical trajectory, precisely because they were neither mass rave events nor sponsored and government-funded festivals. Often anarchic though organised, but always underfunded (usually by student loans and credit cards) and driven by desire alone, such events—in the true sense of the word—pose an important site of EDMC research, precisely because they defy both their high-and-low art designations, and as a result, are often excluded from the storylines of both because of their refusal to abide by the narratives of either.

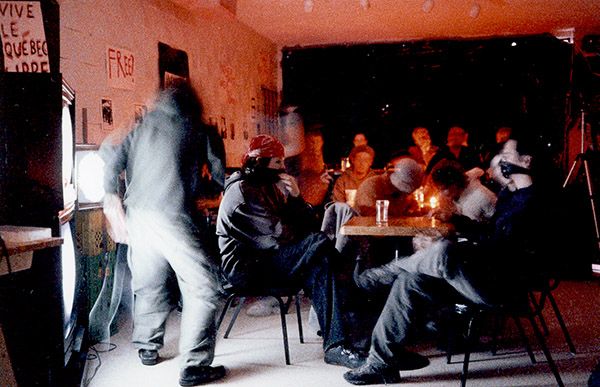

Figure 3. Video-artist Merlyn Chipman performing at unclassifiable, techno-anarchist performance event MUSIKAL RESISTANCE, held during Mayworks 2000, a collaboration of <ST> Collective and the Marginalized Workers Action League (MWAL). Photo credit: Tanya Goehring.

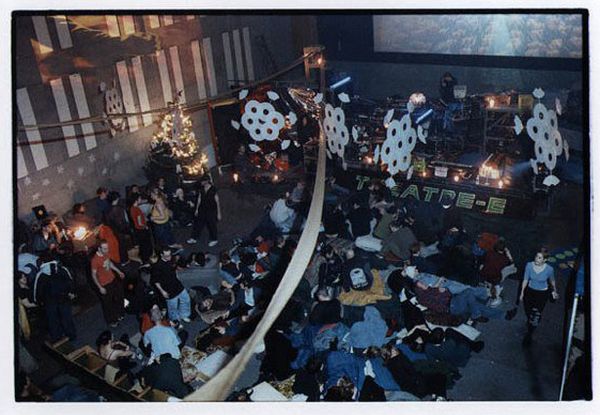

Mixed-media installations and electronic performances in multi-day-and-night formats were central to Vancouver’s technoculture underground that mixed media arts, hacktivist and rave scenes through ad-hoc organisational efforts in unsanctioned spaces. With the aging-out of rave culture around the year 2000, this nascent, mixed and unconstituted scene resituated itself on the fringes of Vancouver’s artist-run centres, universities, club, rave and contemporary art crowds, with several independent events and performance-oriented conferences taking place thanks to the efforts of ad-hoc collectives, such as Refrains: Music Politics Aesthetics (2001), in collaboration with Vancouver New Music.

Figure 4. Kim Cascone performing at Refrains: Music Politics Aesthetics. Photo credit: Tanya Goehring (2001).

Unconventional spaces such as The Butchershop, Open Studios, and Memelab, featuring organisational efforts of renegade media arts curators such as Jesse Scott, ssiess, and olo j. milkman—among others whom I apologise for not mentioning here—but also soon-to-be-closed media arts venues The Blinding Light and the beloved Sugar Refinery, were integral to developing mixed-media aesthetics outside of the constraints of both club culture and gallery settings. Indeed, it is because of the collective productions I had undertaken—with others—in Vancouver’s otherwise nonexistent “media arts” scene that I had been tapped by the NFF to curate the first electronic component of its 2002 edition.[2] Drawing from rave culture lineups and interventionist media and performance arts, the radical, mixillogical style of blending electronic music, performance, installation and conferencing—of, in short, mixing high-brow with low-brow, exhibit-gazing with ritual dance, theory with techno, in what was to become the template for the NFF as a whole—was prototyped at Glitch & Granular. The intense lineup of electronic artists exploring diverse performance modes, from interactive installation to live cinema, evidently influenced many—including the festival’s entire mission, in a one-night happening-styled event.[3] What I want to emphasise, however, is that Glitch & Granular was the culmination of a long trajectory of experimentation that had already charted a radical mixing of sonic/politics/aesthetics in immersive as well as interventionist environments, indeed far in excess of what was staged at NFF that year.

Figure 5. The author DJing at MUSIKAL RESISTANCE. Photo credit: Tanya Goehring (2000).

The NFF’s autobiographical timeline is worth revisiting, in part because I believe the recurring tale of Vancouver’s collective unconscious—which is to say that of any metropolitan city that thinks itself as the “global periphery” and belittles itself accordingly—is that it feels the need to officially import its inspiration from elsewhere instead of recognising (and respecting) the energies of its own. Yet neither Berlin, nor Montréal, were necessary for developing the city’s immersive media arts that combined electronic music with live cinema and avant-garde performance. It is here that an undocumented project remains, and one I have scarcely begun in my own efforts towards scholarly publication: that of telling the tales of Vancouver’s acid house, industrial, techno and post-rave media arts scenes, as well as tracing their influence upon global rave and media arts networks. This story cannot be confined to Vancouver alone; it is already a narrative of global affiliations, from Robert Shea’s early representation of Harthouse Records on the West Coast and the artistic exchanges brought by Skinny Puppy’s success with Vancouver-based Nettwerk Records. But it also includes quieter tales, such as DJ and producer exchanges instigated through Toronto’s techno.ca email list with Vancouver’s techno scene; and the significant cultural force that was the NorthWestRaves (NWR) email list, hosted by Hyperreal.org, and the many events produced by its online/offline community that connected various soundsystem collectives and ravers along the West Coast from Vancouver and Seattle through Portland.

Figure 6. The chill room at NorthWestRaves event <de.lurk>, Seattle. Photo credit: Hyperreal.org (1999).

In Vancouver, many industrial, techno and acid house DJs and crews had been exploring mixed-media events since the 1980s, with Skinny Puppy but also ambient pop group Perfume Tree pioneering mixed-media electronic music performances. In the 1990s, underground collectives such as TeamLounge, B-Side, HQ Communications and <ST> collaborated on numerous events exploring what lay beyond the simple pleasures of hedonistic rave culture, suggesting links between collectivist, ecological and anarchist politics at soundsystem events. Several artist-run centres were likewise at the forefront of establishing mixed-media arts, including The Western Front, with its origins as a West Coast outpost of the Fluxus network. In particular during the late 1990s and early ‘aughts, CiTR 101.9FM and CJSF 90.1FM campus and community radio, along with DiSCORDER magazine, formed a hub for such activities. CiTR’s influential “Art’s Birthday” radio-art broadcast, coordinated by sound artist Anna Friz in partnership with the Western Front and Austria’s Kunstradio, became a meeting ground for radio-art and transmission arts in the city, resulting in performances linking media artists across Canada and beyond (such as this Silophone performance conducted with [The User]). Likewise, CiTR’s radio-art DJs were local catalysts, such as Brady Marks, who founded the Open Circuits Festival of experimental electronic music around 2001, drawing from events of the Intermission Artist’s Society founded in 1999.

Figure 7. Immersive audiovisual environment at TeamLounge ambient event XMAS II. Photo credit: TeamLounge (1998).

Though in an already internet-saturated era all of Vancouver’s media artists were influenced by the world at-large—and of course through the distribution networks of vinyl records and the travels of artists themselves—the process was more of an exchange and mutation of concepts than simply copycatting what went on elsewhere. The NFF didn’t invent the media arts festival in Vancouver, nor did it import it from Transmediale. Thanks to various collective efforts that I can only hope to outline briefly here, its curators built upon the efforts of numerous others who have mostly toiled away in obscurity. It is an unfortunate sign when local efforts, collaborators and precursors remain unacknowledged in any festival’s timeline. This is as unfortunate for the veracity of the festival’s history as it is for the future of the community it situates itself within.

tobias c. van Veen is SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Communications at the Université de Montréal and Visiting Tutor at Quest University. Writing in both popular and academic publications, tobias explores political imaginaries of becoming, indigenous and Afrofuturisms, practices of exodus in electronic dance music cultures and alien phenomenologies. Tobias is editor of the Afrofuturism special issue of Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture (2013) and co-editor with Hillegonda Rietveld of the forthcoming special issue “Echoes from the Dub Diaspora” (2015). A techno-turntablist and practitioner of interventionist media arts since 1993, tobias is also creative director of the IOSOUND.ca music label and resident DJ of Ion Storm podcast at djtobias.com. Tobias has collaborated with festivals and media arts centres worldwide as Founding Director of UpgradeMTL.org and Concept Engineer at the Society for Art and Technology (SAT) in Montréal. Tobias holds an Ad Personam PhD in Philosophy and Communication Studies from McGill University. He tweets @fugitivephilo and blogs at fugitive.philosophy.

[1] “In early 2003, Malcolm Levy was invited to the international media art festival Transmediale. There, he got to see the reality of what NFF was trying to create playing out, with club nights, exhibitions, and conferences all happening cohesively. With this experience, Levy felt the solidification of NFF’s vision”.

[2] See Olo J. Milkman’s archive for images of the previous events held at Video-In (VIVO) before the NFF’s Glitch & Granular.

[3] Also a note on the timeline: I was the moderator and a presenter at the panel with DJ Spooky at Vancouver’s Sonar club that year.